AI-Powered Curriculum Development: How New Universities Can Build Accreditation-Ready Programs in Weeks, Not Months

2026 Evolution of Courseware in Higher Education: From Textbooks to Digital Ecosystems

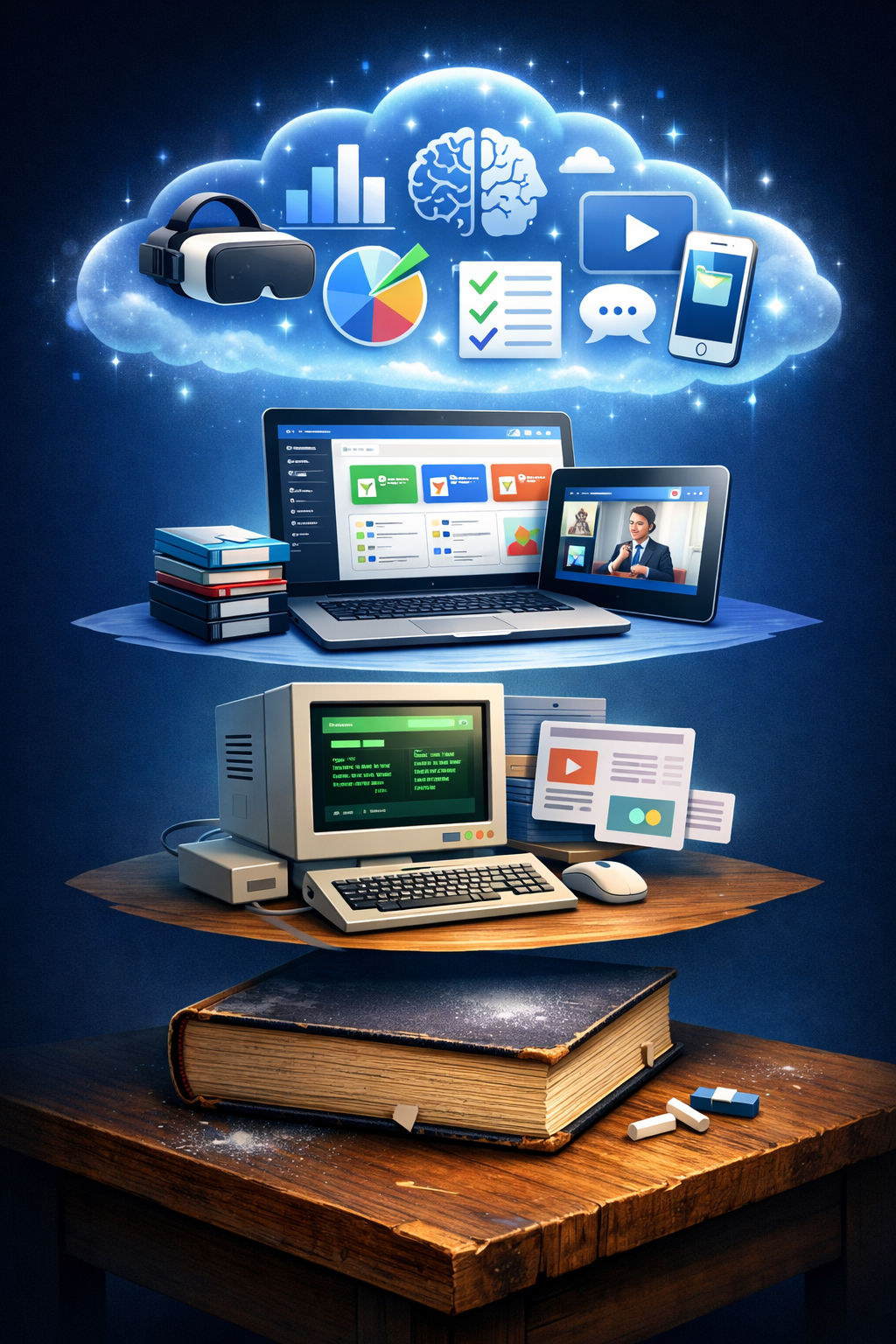

Higher education course delivery has transformed dramatically over the past few decades. For centuries, the printed textbook reigned as the primary courseware – a static repository of knowledge that students carried to class. In the 21st century, however, we are witnessing seismic changes in course materials as universities incorporate more and more digital tools. From chalkboards and heavy textbooks to interactive e-courseware and integrated learning platforms, the evolution of courseware in higher education reflects broader shifts in technology, pedagogy, and student behavior. This comprehensive exploration traces that journey – highlighting key milestones in instructional technology, the rise of Learning Management Systems (LMS), and how student learning behaviors have adapted in the era of digital ecosystems.

From Textbooks and Chalkboards to Early EdTech

For generations, university learning centered on in-person lectures and printed materials. Textbooks have been a staple of higher education since at least the 16th century, and by the 19th century they were firmly established as essential learning tools. In the traditional paradigm, a course’s “courseware” meant a bundle of printed textbooks, syllabi, lecture notes, and perhaps photocopied course packets. Instruction was delivered on chalkboards or overhead projectors, and students took notes with pen and paper. This analog model dominated well into the late 20th century.

Early forays into educational technology: The desire to enhance or replace purely print-based instruction with technology is not new. As early as the 1920s and 1950s, visionary professors experimented with mechanical teaching devices. For example, Sidney Pressey’s 1924 “Automatic Teacher” machine presented questions in a multiple-choice format and gave immediate feedback. In the 1950s, B.F. Skinner introduced the “GLIDER” teaching machine to enable programmed learning with step-by-step reinforcement. Parallel to these devices, educators leveraged mass media – radio and television – to broadcast educational programs, expanding reach beyond the physical classroom. Each of these early technologies represented a small step from the static textbook toward a more interactive learning experience.

Computer-based learning emerges: The 1960s saw the advent of computer-assisted instruction, a precursor to today’s digital courseware. A landmark development was the PLATO system (Programmed Logic for Automatic Teaching Operations), developed at the University of Illinois in 1960. PLATO ran on a mainframe and delivered course content via computer terminals, originally aimed at improving literacy. Over the next decades, PLATO expanded to include features like message boards and email – even early forms of online community – and it inspired future educational software platforms. In fact, the PLATO project’s innovations foreshadowed many elements of modern e-learning, from discussion forums to interactive quizzes. By 1968, universities were offering courses via computer networks; for instance, the University of Alberta delivered 17 classes to over 20,000 students using an IBM system – arguably the first example of online coursework in higher education. These experiments demonstrated that “distance learning” could happen through electronic screens, not just postal mail.

Courseware goes digital (in small steps): Despite these early innovations, for most of the 20th century the core course materials remained physical. Professors might distribute printed lecture notes or assign journal articles, but the primary source of content was still the textbook. By the 1980s and 90s, personal computers became more common on campuses, and with them came new forms of courseware. Professors began using presentation software (e.g. PowerPoint in place of overhead transparencies) and electronic course reserves in libraries. CD-ROMs supplemented textbooks with multimedia content. Some forward-thinking instructors set up class listservs or used course websites to share materials. All of these changes were incremental, but they set the stage for a more radical shift: the rise of the Learning Management System.

The Rise of Learning Management Systems (LMS)

The late 1990s marked a turning point with the emergence of Learning Management Systems – software platforms designed to organize and deliver online course content. The first generation of LMS platforms appeared in the mid to late 1990s. Early pioneers included proprietary systems like WebCT (launched in 1997) and Blackboard (founded 1997), as well as open-source projects like Moodle (first released in 2002). These systems provided a centralized, web-based environment where instructors could upload course materials, assignments, and quizzes, and where students could interact outside of class.

Widespread adoption in higher ed: Initially, LMS usage was experimental, often initiated by tech-savvy faculty or specific departments. But within a decade, LMS platforms became nearly ubiquitous in colleges and universities. In fact, LMSs have now been adopted by almost all higher education institutions in the English-speaking world. By the mid-2000s, many institutions made an LMS a standard part of the campus IT infrastructure, simplifying the management of course websites and online gradebooks. The growth was rapid: one historical account notes that by 2014, Blackboard alone was being used by over 17,000 schools and organizations in 100 countries. The concept of a “course website” evolved from a simple syllabus page to a full-featured digital extension of the classroom.

How LMS changed course delivery: The introduction of LMS technology fundamentally expanded what courseware could encompass. Instead of relying solely on textbooks and face-to-face lectures, instructors could now upload slides, readings, and multimedia content to the LMS for students to access anytime. Discussion forums enabled class conversations to continue between sessions. Quizzes and assignment dropboxes allowed assessments to be conducted (and graded) online. Crucially, LMSs also track and organize student progress, enabling instructors and administrators to monitor engagement and performance across an entire class. In short, the LMS became the new backbone of course delivery, blending content, communication, and assessment into one digital hub

Integration and standards: As LMS usage grew, so did the need for standards to integrate various tools and content. Early on, institutions and vendors worked on interoperability standards like IMS and SCORM to allow course content or modules to be shared across systems. This paved the way for an ecosystem of plugins and external learning tools (from plagiarism checkers to video conferencing) that could plug into an LMS. Over time, the LMS became not just a repository for PDFs, but a launchpad for a multitude of digital learning activities – a place where a student might watch a lecture capture, take a quiz, participate in a simulation, and collaborate on a group wiki all within a unified interface.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: While LMS adoption was high even before 2020, the global pandemic underscored its critical importance. When COVID-19 forced campuses to close in early 2020, virtually every institution pivoted to remote instruction – and the LMS was the immediate vehicle for this transition. An estimated 98% of higher education institutions moved the majority of their classes online by April 2020. Instructors who had never taught online had to quickly post materials, hold discussions, and assess students through platforms like Canvas, Blackboard, or Moodle. This abrupt shift accelerated the maturation of digital course delivery. By necessity, nearly all faculty and students became intimately familiar with online learning tools. Surveys after the first pandemic semesters showed that a majority of learners felt their LMS was instrumental in sustaining learning during the crisis. The pandemic, in effect, cemented the LMS (and the broader digital ecosystem around it) as an indispensable component of higher education. Even as campuses reopened, both students and faculty expressed eagerness to continue using many of the digital tools adopted during the pandemic.

From Print to Digital: The Evolution of Textbooks and Course Content

One of the most visible shifts in courseware has been the move from traditional print textbooks to digital and interactive content. For decades, students would line up at the campus bookstore each term to purchase expensive stacks of textbooks. Today’s students, however, are increasingly likely to access their course readings via e-textbooks, learning apps, or online course packs. This transition has been driven by a combination of technological innovation, cost pressures, and changing student expectations.

The digital textbook revolution: The concept of electronic textbooks has been around for longer than many realize – the first e-book was created in 1971 as part of Project Gutenberg’s efforts to digitize texts. But it wasn’t until the 2000s that e-textbooks began to gain real traction in higher education. A major catalyst was the soaring cost of college textbooks. Between 2002 and 2012, textbook prices rose 82% – outpacing inflation and becoming a significant financial burden on students. In response, students sought alternatives: many delayed or avoided purchasing required books due to cost, turned to used book markets, or tried new rental services. Publishers and policymakers took note. Notably, in 2009 California’s governor at the time, Arnold Schwarzenegger, launched an initiative to promote free open-source e-texts in schools as a cost-saving measure.

E-textbooks go mainstream: By the 2010s, virtually all major textbook publishers were offering digital versions of their titles. Devices like Amazon’s Kindle and Apple’s iPad provided convenient platforms for reading e-books. In fact, Apple’s release of the iPad (and the iBooks app) around 2010 was hailed as a turning point that propelled the e-textbook forward. These digital texts were not mere PDFs; they often came enriched with multimedia and interactive features. Apple even introduced an authoring tool, iBooks Author, to help create multimedia textbooks with videos, quizzes, and interactive diagrams. Educators and even institutions began to produce their own e-texts, customizing content for their courses.

Advantages of digital course content: The appeal of digital courseware is multifaceted. First, there’s convenience and cost. Digital textbooks are accessible on laptops or tablets – far easier to carry than a backpack full of books. They are often cheaper than print; for example, an electronic textbook might cost $30 less than its new hardcover counterpart. Second, digital content can be updated more easily, ensuring students have the most current information without waiting for new print editions. Third, the interactive capabilities of e-courseware can enhance learning. A digital textbook can embed videos, 3D models, or self-check quizzes directly into the reading experience. Many e-textbooks now include features like highlighting, note-sharing, and search functions that make it easier for students to study and collaborate. Research has suggested that such features, when used, can improve engagement – for instance, interactive quizzes provide real-time feedback and help students identify what they do or don’t understand. Furthermore, because digital platforms can collect data on usage, instructors can gain insights via learning analytics (e.g., seeing which chapters students spend the most time on, or where they struggle), enabling a more data-driven approach to teaching.

Open Educational Resources (OER) and courseware: Alongside commercial e-textbooks, the past two decades saw growth in open courseware and open educational resources. A landmark event was MIT’s launch of OpenCourseWare in 2001 – a platform to publish materials from actual MIT courses for free public access. This bold move demonstrated the potential of the internet to disseminate high-quality academic content well beyond enrolled students. Following MIT’s example, many universities and individual faculty began sharing lecture notes, slides, and even full textbooks openly. These OER materials provide low-cost (or no-cost) alternatives to traditional textbooks. By the mid-2010s, entire degree programs were experimenting with “open textbook” curricula to save students money. Some governments and foundations also funded the development of open textbooks for popular general education subjects. While OER adoption in higher ed has been gradual, it represents an important facet of the courseware ecosystem – one that emphasizes accessibility and collaboration.

Challenges and the state of adoption: Despite the advantages, the shift to digital course materials hasn’t been entirely smooth. Early studies in the 2010s found that student uptake of e-textbooks was modest and many students still preferred print, citing reasons like eye strain or difficulty annotating digital text. In 2012, only about 5% of U.S. institutions had a campus-wide e-textbook program, though many more were experimenting on a smaller scale. Platform fragmentation was one issue – different publishers and providers used different apps or formats, leading to a non-uniform experience. Moreover, some interactive e-texts were limited to certain devices or lacked offline access, frustrating students used to the reliability of print. Another key factor is instructor integration: research indicated that if professors didn’t actively incorporate the e-textbook into their teaching (for example, showing students how to use its features or assigning digital-only content), students were less likely to fully switch over from print. Over time, these issues have been gradually addressed. Platforms have become more standardized (e.g., the PDF and ePub formats, or publisher platforms that integrate with the LMS). Students have also become more accustomed to digital reading – especially as K–12 schools increasingly use tablets, incoming college students expect digital options. By the late 2010s, surveys showed well over half of college students had used an e-textbook in at least one course, and the number continues to rise.

Publishers’ new models: Facing the decline of print textbook sales and competition from used-book markets, publishers have pivoted to digital courseware models. Many now offer inclusive access programs, where students pay a course fee that gives them immediate digital access to textbooks and homework platforms on the first day of class. This model, often integrated through the LMS, ensures every student has the required materials (in digital form) while typically offering a lower price than a new print book. Additionally, publishers have developed sophisticated online homework systems (like Pearson MyLab, McGraw-Hill Connect, or Cengage WebAssign) that go beyond the e-book, providing problem sets, virtual labs, and adaptive tutoring aligned with the textbook. By 2018, Cengage even launched a subscription service (“Cengage Unlimited”) granting students access to its entire digital textbook catalog for one flat subscription price – an approach that echoed the Netflix model applied to textbooks. These integrated products blur the line between “textbook” and “course platform,” effectively becoming full courseware ecosystems provided by a single vendor.

In summary, the journey from print to digital course content has been driven by the need to improve affordability, accessibility, and pedagogical effectiveness. While physical textbooks are still in use and likely won’t disappear overnight, their dominance has eroded. As one analysis noted, it is unlikely that print textbooks will “regain their foothold” given the digital-first strategies of publishers and the preferences of today’s students. That said, the transition continues to take into account equity concerns – not all students have reliable access to devices or internet at all times, raising the importance of addressing the digital divide even as we move toward fully digital courseware.

Integrated Digital Ecosystems: Courseware in the 21st Century

As universities layered more technology into teaching, a digital ecosystem for learning began to emerge. In this context, a digital ecosystem refers to the interconnected web of platforms, tools, and resources that deliver a seamless learning experience. It goes beyond a single application; it’s the fusion of the LMS with numerous integrated tools – from lecture capture systems to digital libraries to mobile apps and analytics dashboards. Over the past decade, higher education has evolved from using discrete tech tools to building holistic ecosystems that support teaching and learning.

The LMS as the hub: In a modern course, the LMS often serves as the central hub of the digital ecosystem. But it is now typically connected to a range of specialized tools. For example, a course’s LMS site might include a link to join a live class session on a video conferencing platform, an embedded quiz powered by an external assessment tool, a plugin that checks assignment submissions for plagiarism, and integration with the university’s library databases for course readings. Thanks to standards like LTI (Learning Tools Interoperability) and APIs, today’s LMS can “talk” to countless third-party applications. This integration ensures students and instructors navigate a seamless digital environment rather than a disjointed set of logins. Effective digital ecosystems are characterized by single sign-on access and interoperability across devices – so a student can switch from viewing a lecture on their laptop to revising flashcards on their phone without losing progress.

Key components of the ecosystem: Beyond the LMS itself, some common components of a higher-ed digital learning ecosystem include:

- Lecture capture and videos: Many institutions use systems (like Panopto, Kaltura, or Echo360) to record live lectures or create supplemental videos. These integrate with the LMS so that students can stream class recordings or tutorial videos on demand. The importance of video has grown – surveys show 83% of people prefer watching an instructional video to reading text for learning how to do something, making video an essential part of courseware today.

- Collaboration and communication tools: These range from discussion forums (often within the LMS) to real-time messaging apps or dedicated group-work tools. Especially after the pandemic, tools enabling online interaction have proliferated. In fact, during the shift to remote learning, adoption of tools that support connectivity and community-building (like discussion boards, group chat channels, virtual study rooms) spiked by 49% – the largest uptake among learning technologies – as they filled the void of in-person interaction. This shows how critical the social dimension is in digital courseware ecosystems.

- Assessment and feedback tools: Digital ecosystems support both formative and summative assessments. Quizzing tools, online proctoring systems for exams, and e-portfolio platforms all play roles. What’s notable is how assessments are now often tightly integrated with learning resources. For instance, adaptive learning platforms give students practice questions that adjust in difficulty based on their performance, offering hints or remediation as needed. Meanwhile, instructors receive analytics on student performance in real time, allowing them to identify learning gaps quickly. The ecosystem thus enables a feedback loop that was hard to achieve with static textbooks and periodic exams.

- Analytics and learning intelligence: One of the promises of a digital ecosystem is the data it generates. Modern courseware platforms can track a student’s clicks, time spent on tasks, quiz attempts, discussion contributions, and more. Many universities are leveraging these data through learning analytics dashboards that help advisors support at-risk students and help instructors refine their teaching. For example, an instructor might see that a majority of the class spent very little time on a reading that was critical to an assignment – indicating either the reading was skipped or not understood – and can then address that in the next class. The integration of adaptive learning technologies means some systems even personalize the pathway of content for each student, using AI to recommend next activities or to target weak areas.

- Mobile and on-the-go access: Today’s students expect to be able to check grades, read discussion posts, or watch lectures from anywhere. Thus, a robust digital ecosystem ensures mobile compatibility. Most LMS platforms now have mobile apps, and many digital textbooks are accessible via e-reader apps. The emphasis on mobile is for good reason: learners often take advantage of small pockets of time to study on phones or tablets, and studies have found a significant portion of students (e.g. 42% in some surveys) use smartphones for academic purposes in the classroom or for coursework. A well-integrated ecosystem maintains functionality across devices, allowing continuity of learning whether a student is at a computer lab or on a bus with a phone.

Campus-wide integration: At an administrative level, the digital learning ecosystem is also tied into other campus systems. The LMS might sync with the student information system (SIS) to roster students into courses and report final grades. It may connect with the library system for authentication to databases or e-reserves. Increasingly, universities talk about the learning ecosystem as part of the broader campus digital ecosystem that also includes enrollment, advising, and even co-curricular tools. The ultimate goal is an integrated experience for students from admission through graduation, where all the digital touchpoints – academic and administrative – are connected. This has strategic importance for university leaders (like provosts and deans) who oversee technology adoption. They are looking to ensure that investments in technology lead to better learning outcomes, greater student engagement, and operational efficiency.

Continuous evolution and future trends: The concept of a digital ecosystem in learning is continually evolving. In recent years, we’ve seen rising interest in technologies like virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) for immersive educational experiences, and these are being connected to courses in innovative ways (for instance, a biology class using VR labs). Similarly, intelligent tutoring systems and AI-driven chatbots are beginning to find a place in higher ed courseware. These AI tools can handle routine student questions or provide personalized tutoring, complementing the instructor’s role. The use of AI in e-learning platforms is making learning experiences more adaptive; AI can recommend study resources or adjust difficulty based on a learner’s pattern of answers. All these elements suggest that the digital ecosystem model will become even more intelligent and personalized in the coming years.

However, building and maintaining a digital ecosystem comes with challenges. Universities must navigate issues of data privacy and security (when so much learning activity is digital, protecting student data is paramount). There’s also the challenge of training faculty and students to effectively use the tools – a cutting-edge platform is of little use if instructors aren’t comfortable integrating it into their pedagogy. As noted in one report, successful digital integration requires investing in educator training and aligning new tools with curriculum goals. Furthermore, the more complex the ecosystem, the more important it is to have reliable support and to avoid technical glitches that can disrupt learning.

In essence, higher education’s courseware has evolved from a single-textbook model to an ecosystem model. Course content is now dynamic and multifaceted, delivered through a network of interconnected systems. For university administrators, this means thinking about technology adoption not as purchasing individual products, but as nurturing a compatible suite of tools that together enhance teaching and learning.

Trends in Instructional Technology and Course Delivery

The evolution of courseware cannot be separated from broader trends in instructional technology and pedagogy. As new tools became available, educators explored new teaching methods, and student expectations evolved in tandem. Let’s look at some key trends and how they influenced course delivery in higher education:

1. Blended and hybrid learning: One significant trend over the past two decades is the rise of blended learning – combining face-to-face instruction with online components. As LMS and digital content became common, many courses shifted to a hybrid format (even before the pandemic made hybrid a necessity). For example, a professor might hold in-person classes twice a week and have students complete online modules or discussions in lieu of a third meeting. This model leverages the strengths of both modes: the rich interaction of the classroom and the flexibility and resources of the online environment. By 2019, even before the COVID-19 disruptions, a large portion of students had experienced at least one online or blended course. In fact, surveys indicated that 90% of students preferred learning that included online elements over traditional purely face-to-face methods, and nearly half had taken an online course during their college career. The prevalence of blended learning has only grown, and it points to an important realization – digital courseware was not meant to replace the classroom, but to enhance and augment it.

2. Active learning and flipped classrooms: Technology has also enabled a shift from passive learning (students simply listening to lectures) to more active, student-centered learning. The flipped classroom model is a prime example. In a flipped class, students first encounter new material at home (often via video lectures or online readings), and then class time is used for discussion, problem-solving, or other interactive activities. LMS and video platforms made it feasible for instructors to easily share recorded mini-lectures or curate tutorial videos for students to watch before coming to class. This approach has been widely adopted in universities for subjects ranging from physics to nursing. The LMS supports it by providing a venue for quizzes or reflections on the videos, ensuring students prepare. Research suggests that these methods can improve engagement and learning outcomes, as students spend class time applying knowledge rather than just receiving it. Notably, modern LMS features like quizzes and adaptive release (where a video’s subsequent section only unlocks after a student answers a question) support the flipped model by keeping students accountable for the pre-class work.

3. Growth of online programs and MOOCs: A major trend in course delivery has been the expansion of fully online programs and the advent of MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses). Universities that once only offered on-campus degrees began launching online degree programs in the 2000s to reach wider audiences. By the end of the 2000s, millions of students were enrolled in online courses. (For instance, by fall 2009 about 5.6 million U.S. students were taking at least one online course, representing roughly 30% of total enrollment – a number that grew each year after.) Then in 2012 came the MOOC revolution, with platforms like Coursera, edX, and Udacity offering free courses to anyone in the world. The New York Times dubbed 2012 “the Year of the MOOC” as top universities opened up courses to global audiences, sometimes attracting tens of thousands of learners to a single class. While MOOCs are often not part of for-credit courseware at a student’s home institution, they influenced higher education by showcasing new approaches (such as scalable peer grading and automated assessment) and by pressuring colleges to innovate their own online offerings. The MOOC movement also accelerated universities’ engagement with video lectures, short modular content, and forums – all elements that have trickled into mainstream courseware. Today, many instructors incorporate open resources or even reuse materials from MOOCs and other online repositories in their on-campus classes, effectively blending the open courseware world with their own teaching.

4. Interactive and adaptive learning tools: Another trend in instructional tech is the use of interactive software and simulations to teach concepts that were once taught via static text or live demonstration. For example, business courses might use simulation games where students make decisions and see outcomes, language courses might use apps that provide immediate pronunciation feedback, and science courses might use virtual labs or interactive diagrams that let students experiment in a risk-free environment. These tools are increasingly part of the courseware bundle. Adaptive learning systems, in particular, have gained traction for large general-education courses. These systems tailor the practice questions or even the sequence of content to each learner’s needs – a student who has already mastered a concept can move on quickly, whereas one who is struggling will get additional exercises and explanations. Such personalization, often powered by AI, represents a significant advancement in courseware, moving away from one-size-fits-all textbooks to a more responsive learning journey. Studies are ongoing, but early implementations show promise in improving student outcomes, especially in foundational courses where students’ incoming skill levels vary widely.

5. Classroom engagement tech: Inside physical classrooms, technology has changed the dynamics of lecture delivery. In the early 2000s, clickers (personal response systems) became popular – handheld devices or phone apps that allowed students to vote or answer multiple-choice questions during class. This gave instructors real-time feedback and kept students engaged (e.g., through live polls or quizzes). Today, such functionality is often integrated into lecture presentation software or web apps, and students can use their own devices to participate. Interactive whiteboards and smart boards replaced traditional chalkboards in many classrooms, enabling instructors to project digital content and annotate it on the fly. These boards often interface with software to save notes or incorporate multimedia. Such tools make the boundary between online and offline learning – a professor might solve problems on a smart board and then upload the annotated notes to the LMS for students to review later.

6. Data-informed teaching: A subtler trend is that instructors now have access to much more data about student learning, and this is beginning to inform instructional design. For example, an instructor might look at LMS analytics before class and discover that, say, 20% of students haven’t logged in to view that week’s readings, or that the average score on the last online quiz was 60% indicating a misconception. As a result, the instructor can adjust the day’s lesson to address those gaps. On a program level, departments can see patterns like which courses have high dropout or failure rates and investigate if courseware changes (perhaps introducing an adaptive tutorial or supplemental online module) can help. The mantra “learning analytics” has gained traction in higher ed administration as part of using technology to improve student success. Of course, using these data effectively requires faculty development and administrative support, but the potential is there. A 2024 study of online learning leaders found that 60% observed online classes filling up faster than face-to-face, suggesting students see value in these modalities. Such insights encourage administrators to invest more in online and hybrid offerings. In another survey, 74% of U.S. learners said that their LMS and online tools have improved their learning experience, a statistic that administrators can hardly ignore when planning for the future.

Through these trends, one can see an overarching theme: instructional technology has consistently pushed toward more flexible, student-centered, and data-rich teaching methods. Courseware has evolved from a static product (a textbook and a printed syllabus) to a responsive service (an assemblage of content and tools that adapts to how students learn). For faculty and instructional designers, this means that developing a course now often involves curating a mix of resources – some created by the instructor, some publisher-provided, some open-source, and some student-generated – all delivered via a tech-enabled framework that can evolve during the course. The role of the instructor is shifting from solely being a content expert delivering information, to being a designer of learning experiences and facilitator/coach, using digital courseware to enhance student engagement and understanding.

Shifting Student Learning Behaviors in the Digital Age

Perhaps one of the most important aspects for university leaders to consider is how student learning behaviors and expectations have changed alongside the evolution of courseware. Today’s college students are often characterized as digital natives – having grown up with the internet, smartphones, and instant access to information. Whether or not one fully accepts that label, it’s clear that the way students approach studying and learning in 2025 is markedly different from a generation ago. The transformation of courseware and the transformation of student habits go hand in hand.

Expectations of immediacy and access: Modern students expect academic information to be available on-demand. In practical terms, this means they anticipate that course materials will be posted online (ideally accessible 24/7 and from any device), that grades and feedback will be delivered through online systems promptly, and that if they have a question outside of class, they can reach out via email or discussion board and find answers relatively quickly. This is a stark contrast to decades past, where if you missed a class or lost a handout, you had to borrow notes or visit office hours. Now, with robust LMS usage, students rely on having the syllabus, slides, and even lecture recordings at their fingertips. This expectation has even influenced enrollment decisions – many students consider the availability of online resources and the tech-friendliness of a university as factors in their satisfaction. In fact, as noted earlier, a vast majority of students express preference for courses with online components, with convenience often cited as a major reason.

Study habits and resource usage: Students today leverage a wide array of digital resources for learning, often in addition to (or instead of) traditional textbooks. They are apt to look up tutorials on YouTube, use flashcard apps like Quizlet, or engage in online study groups via social media or messaging platforms. The formal courseware ecosystem has expanded to include some of these practices; for example, many instructors now curate YouTube videos or use open online simulations as part of assignments. Moreover, students are adept at information retrieval – rather than reading a whole chapter to find a specific concept, they might use the search function in an e-textbook or skim lecture slides uploaded to the LMS. This doesn't mean students have shorter attention spans per se, but it does indicate a more non-linear approach to learning content. Courseware designs have responded by chunking information into smaller segments (microlearning units, short videos, etc.), which align with how students tend to consume content in the digital age. The statistic that the average preferred length of an instructional video is around 10–15 minutes reflects this tendency toward short, focused bursts of learning.

Collaborative learning and peer interaction: Technology has made it easier for students to collaborate outside of class. Many courses now formally incorporate group projects that use collaborative tools (like Google Docs, shared online workspaces, or LMS-based group areas). But even when not assigned, students often create their own virtual study circles – GroupMe chats for a class, Facebook groups to share study guides, etc. The social aspect of learning has increased. Recognizing this, instructors and course designers have added more collaborative elements into courseware, such as peer review assignments, discussion forums, and group quizzes. During the pandemic era, when isolation was a concern, institutions saw how important these online communities were. Technologies that enabled community building had the biggest jump in usage among learning tech during COVID. A caring, connected learning network – even if partly or fully online – improves student motivation and persistence.

Self-paced and personalized learning: With the abundance of resources online, students have become more self-directed in some respects. If a concept in class isn’t clear, a student might quickly find an explanatory video or an alternate textbook chapter online that clarifies it. This on-demand help-seeking is a positive development, and modern courseware often facilitates it (for instance, some digital textbooks include links to supplementary materials, or the LMS might have a Q&A forum where students can get help any time). Additionally, many students appreciate the flexibility of self-paced learning modules that allow them to progress at their own speed. When given the chance, students will sometimes work ahead in an online course module or, conversely, review earlier modules repeatedly until they feel confident. This contrasts with the lockstep pace of traditional lecture courses. Universities have started to respond by offering more asynchronous course components and even fully self-paced online courses for certain subjects. As one indicator, more than 60% of chief online officers reported that online classes tended to fill up before the equivalent face-to-face sections, suggesting that students are drawn to the flexibility and possibly the self-paced aspects of online learning.

Multitasking and focus: On the flip side, the digital environment comes with distractions. Students are often multitasking – toggling between a lecture video and social media, or doing coursework while responding to messages. This has raised concerns about attention and depth of learning. Effective digital courseware design tries to mitigate this by increasing interactivity (keeping students engaged through frequent quizzes or tasks) and by training students in digital literacy and time management. Some instructors now explicitly teach students how to study in an online setting, including how to minimize distractions. The issue of focus is an ongoing challenge: technology gives and technology takes away. Provosts and deans are increasingly aware that student support services must evolve to include coaching on how to learn effectively with technology (for example, how to take good notes from video lectures or how to schedule one’s week for an online-heavy course load).

Orientation to technology: It’s worth noting that while today’s students may be comfortable with apps and devices, they aren’t necessarily versed in every academic technology by default. There is a learning curve with any new system. The majority of institutions provide some form of training or orientation for their LMS and other tools, yet a 2020 EDUCAUSE survey found that 99% of institutions offer LMS/technology support, but many students either did not receive formal training or were unaware if training was available. This suggests that institutions should not assume students will simply “pick up” academic tech skills on their own. To truly benefit from advanced courseware features (like using analytics dashboards for self-assessment, or engaging in elaborate simulation exercises), students often need guidance. The good news is that students are generally quick to adapt once they see the value. For instance, when professors model the use of e-textbook tools (like showing how to annotate or highlighting important sections), students are more likely to adopt the e-text and even prefer it over print.

In conclusion, student behavior has both driven and been shaped by the evolution of courseware. Students today operate in a learning environment of abundance – abundant information, abundant resources, abundant ways to communicate. This can be empowering, enabling more personalized and efficient learning, but it can also be overwhelming without proper scaffolding. University administrators and faculty must understand these behavior shifts to design course experiences that meet students where they are. Courseware, in its modern form, is one of the key interfaces between the student and the institution’s knowledge offerings, so ensuring that it aligns well with student needs and habits is critical.

Conclusion: Courseware’s New Era and What Lies Ahead

The journey from the era of the single printed textbook to the era of digital ecosystems in higher education courseware has been transformative. We have moved from a model where knowledge was locked in physical pages and classroom walls, to one where knowledge flows through networks, across devices, and through interactive platforms. For university leaders – provosts, deans, and other administrators – understanding this evolution is key to making informed decisions about teaching and learning strategies.

Reflections on the transformation: The changes in courseware have broken down many barriers. Geography and time are less limiting now – a student can engage with course materials from anywhere and at any time, a flexibility that has opened doors for non-traditional students and made continuous learning more feasible. The digital shift has also introduced cost efficiencies in some areas (though one must remain vigilant about new costs, such as subscriptions and infrastructure). Most importantly, the integration of technology has the potential to improve pedagogy: real-time feedback, adaptive content, and rich multimedia can address diverse learning styles and needs in ways a static textbook never could. Studies show that well-implemented digital courseware can enhance academic performance by supporting personalized learning and frequent feedback. Furthermore, digital content can be more inclusive – providing accessibility features like text-to-speech, adjustable font sizes, or captions on videos, which help students with disabilities engage fully.

Ongoing challenges: Despite the advancements, the evolution is not complete or evenly distributed. Some faculty and students still prefer traditional materials or find them more reliable (for example, a physical textbook never has a connectivity issue or platform outage). Ensuring equity is a big concern: not all students can afford the latest devices or have high-speed internet at home, so universities must work to provide loaner equipment or on-campus access to bridge those gaps. There is also the challenge of information overload – with so many resources and tools available, students can feel overwhelmed, and instructors might struggle to streamline content. As the courseware ecosystem grows, thoughtful curation and user-centric design become paramount. Simplicity and clarity in how course content is organized can make a big difference in student success; a confusing LMS site can hinder learning as much as a confusing textbook.

Additionally, faculty workload and support need consideration. Creating and managing digital courseware – whether it’s setting up an LMS course site, recording mini-lectures, or monitoring online discussions – demands time and skills. Institutions should invest in instructional design support and professional development so that faculty can efficiently leverage new tools. The human element remains crucial: technology works best when instructors use it purposefully, and when students are guided in its use.

The road ahead – an ecosystem of innovation: Looking to the future, courseware in higher education is likely to become even more integrated, intelligent, and student-centered. We can foresee learning ecosystems that are adaptive not just within a single course, but across a student’s entire curriculum – for example, tailoring degree pathways based on competencies, or using AI to recommend supplemental learning opportunities (like workshops or tutoring) when a student is struggling. Virtual and augmented reality may bring immersive experiences into mainstream education, particularly for fields that benefit from simulation (imagine archaeology students taking a virtual tour of ancient sites, or medical students practicing surgery in VR). Gamification elements might further engage students, turning certain learning tasks into game-like challenges that drive mastery through motivation.

Importantly, data analytics and AI could allow for early interventions at an institutional level – predicting which students might be at risk of failing or dropping out and proactively offering support, something some platforms are already attempting. Such uses of courseware data must be balanced with ethical considerations around privacy, but if done carefully, they can significantly improve student retention and success.

Maintaining the human touch: Amid all this innovation, one must remember that education is fundamentally a human endeavor. Courseware is a means to an end: improved learning. It should amplify the best of what teachers and students can do together, not replace the faculty role or diminish the value of peer-to-peer interaction. The evolution so far shows that technology works best when it complements pedagogy – e.g., freeing up class time for discussion by offloading content delivery to videos, or providing insights that a professor uses to personalize their guidance. University administrators should thus view investments in courseware as investments in enhancing teaching, and ensure that faculty and students are partners in this evolution, not just end-users of edtech products.

Final thought: The shift from textbooks to digital ecosystems in higher education has been profound, and it continues to unfold. Each phase – from the first LMS installations to the emergency remote teaching of the pandemic – has taught the academic community valuable lessons about what works and what doesn’t. As we stand in this new era, the institutions that will thrive are those that take a strategic, learner-focused approach to courseware. This means leveraging the best of technology while upholding academic rigor and inclusivity. It means using data to inform decisions but also listening to student and faculty feedback. The evolution of courseware is not just a story of technology; it’s a story of how a centuries-old enterprise of education adapts and endures. By embracing the opportunities of digital ecosystems and conscientiously addressing their challenges, higher education can create learning experiences that are more engaging, effective, and equitable than ever before – truly fulfilling the promise of this courseware revolution.

For more information about how to get LMS ready courseware for your institution, contact Expert Education Consultants (EEC) at +19252089037 or email sandra@experteduconsult.com.