How AI Changes the Budget: Rethinking “How Much Does It Cost to Open a College or University” in 2026

Opening a Private University: The Recession-Proof Investment

This involves helping our clients understand all the legal and financial requirements around university establishment, as well as providing marketing and branding advice to ensure their university or college stands out from other educational institutions.

Our competitors can only offer a limited service, either licensing or accreditation, as most don't have the skills or team required to provide a turnkey service. This is why EEC stands out from the crowd – we can offer our clients everything they need to get their university off the ground easily and efficiently.

At EEC we're looking at building a long-term relationship with our clients, where launching a university is only the first step.

We are confident that no other company can match our team of experts and their specialized knowledge.

Why This Topic Matters Now

In an era of economic uncertainty, many entrepreneurs and educators are exploring bold ideas to secure their future. One such idea – opening a private university – stands out as a recession-proof investment in both financial and societal terms. But what does “recession-proof” really mean, and why is education often considered timeless in value? Simply put, a recession-proof venture is one that can withstand or even thrive during economic downturns. Education fits this description because learning remains in demand regardless of the economy’s ups and downs. When jobs are scarce, people often turn to higher education to improve their skills and marketability, leading to stable or increased college enrollments during recessions. For example, during the Great Recession of 2008–2009, undergraduate enrollment in the U.S. jumped by nearly 16% as millions pursued degrees amid a weak job market. This counter-cyclical trend shows that education is a safe harbor – when the economy falters, many individuals go back to school, making universities remarkably resilient.

Education’s resilience isn’t just about weathering storms; it’s also about long-term, lasting value. The knowledge and qualifications gained through higher learning never depreciate in the way stocks or real estate might. A college degree can unlock career doors and remains a vital investment in one’s future, offering a transformative journey beyond textbooks and classrooms. In every generation, parents and students prize education as a pathway to opportunity. For centuries, universities have been centers of innovation, personal growth, and societal progress – a testament to the timeless value of education. In short, while trends and technologies change, the fundamental need for learning endures.

Why does this topic matter right now? Coming out of global challenges and economic shifts, there’s a renewed focus on building sustainable ventures that also contribute positively to society. Opening a private university checks both boxes: it can be financially sustainable (even in recessions) and creates a lasting legacy of education. Moreover, the higher education landscape is evolving – with online learning, shifting demographics, and demands for new skills – making now an exciting time to innovate. By understanding how to open a university and why it’s considered recession-resistant, visionary readers can seize an opportunity to impact future generations and secure a stable investment. In the following sections, we’ll demystify the process with clear, friendly explanations and hypothetical stories to make each concept easy to grasp. Whether you dream of opening a college in your community or launching an online university to reach learners everywhere, this guide will walk you through the journey step by step.

Why Private Universities Are Recession-Proof

What makes private universities “recession-proof”? The term might sound like hype, but it essentially means that demand for higher education stays strong even when the economy weakens. Let’s unpack this with examples. Imagine two entrepreneurs in a tough economy: one runs a luxury retail store, and the other runs a small private college. As a recession hits, customers cut back on expensive shopping – the retail store struggles. Meanwhile, the college sees its evening classes filling up with adults learning new skills after layoffs, and high school graduates still knocking on the door for admission. Education is often seen as counter-cyclical: when unemployment rises, many people go back to school instead of sitting idle. During the 2008 recession, for instance, colleges experienced a surge in enrollment as people pursued degrees to improve their career prospects. In other words, higher education benefits from a consistent (and sometimes increasing) demand in hard times, making it more resilient than industries that rely on discretionary consumer spending.

It’s not just about bad times – in good times, the demand for education remains steady as well. Every year, millions of students graduate high school and seek college opportunities. Professionals constantly look for advanced degrees or certificates to get promotions. This creates a baseline demand for universities that doesn’t vanish when the economy dips. For example, a private university offering in-demand programs (like healthcare, technology, or business) will continue to attract students year after year because those skills lead to jobs that society always needs. Even if a recession causes some to postpone college, many others will seize the moment to upskill, knowing that better qualifications can shield them from future economic turbulence. Education is widely viewed as a personal investment in human capital, one that pays off over a lifetime. That mindset doesn’t disappear in a downturn – if anything, it gets stronger.

Another reason private universities can be recession-proof is their flexibility and multiple revenue streams. A well-established private institution might have diverse funding sources: tuition, endowments, research grants, and donations. If one source falters (say, donations drop in a recession), tuition revenue might still hold steady due to enrollment resilience. Moreover, private universities can adapt by offering new programs or short-term courses tailored to economic needs – for instance, adding a certificate in digital marketing when jobs in traditional fields are scarce. Hypothetically, consider a small private college during a recession: it might launch affordable online courses for career switchers, keeping its classrooms (virtual or physical) full while other businesses see empty stores. This adaptability, combined with the enduring allure of degrees, helps private universities maintain stability.

That said, “recession-proof” doesn’t mean completely immune to challenges. Private universities still need sound management. In reality, institutions must be mindful of affordability (students and families feel financial strain during recessions) and competition (students might choose public colleges or online options if budgets are tight). However, the overall trend has shown higher education to be remarkably resilient. Many college towns even experience steadier local economies because universities keep people employed and students spending money year-round. The key takeaway is that opening a university taps into a fundamental, evergreen demand. Educating people is a mission that society continues to support through thick and thin. For an investor or educator, this makes starting a private university not just a noble pursuit, but a strategic one that can weather economic storms while transforming lives.

How to Open a University – Vision, Legal Steps, and Naming

Embarking on the journey of how to open a university can feel like planning a city – it’s complex but immensely rewarding. Every great university begins with a clear vision and a strong foundation. In this section, we’ll cover the early steps: defining your mission, setting up a legal entity, choosing the right state to operate in, and registering a name for your institution. To make it simple, let’s break it down into a few key phases, using friendly explanations and a hypothetical scenario.

1. Crafting Your Vision and Mission: Start with the “why” and “what” of your university. Why do you want to open this institution, and what educational mission will it serve? Imagine you’re an educator named Maria who dreams of creating a college focused on environmental innovation. Maria’s first step is to write down her university’s purpose and goals. Is the goal to foster cutting-edge research, to serve underrepresented students, to offer affordable online education, or something else? Defining your values and principles will guide all other decisions. For example, you might decide your university will “prepare students for the challenges of the 21st century with a focus on sustainability and community engagement”. This vision will influence everything from academic programs to campus culture. Take time to articulate a mission statement – a concise declaration of your university’s core purpose. It’s okay if it evolves, but having a guiding star from the outset is crucial. This is also the stage to consider whether your institution will be non-profit or for-profit, since that can align with your mission (many traditional private universities are non-profit, prioritizing education over profit, whereas a for-profit college might emphasize scale and returns – choose what aligns with your goals).

2. Choosing a Legal Entity: Once your vision is clear, the next practical step is business formation – in other words, creating a legal entity for your university. This is similar to registering any startup or company, except you’ll also be positioning it as an educational institution. Common business structures include forming a corporation or a limited liability company (LLC). For example, Maria could establish her college as a Non-Profit Corporation if she intends to reinvest surplus revenues into the school and potentially seek donations or grants. Alternatively, some founders opt for an LLC or C-Corporation if they have private investors and possibly plan to operate as a for-profit school. Each structure has pros and cons. An LLC or C-Corp provides limited liability protection – meaning your personal assets are protected if the university incurs debts or legal issues. If you’re the sole founder, you could start as a sole proprietorship (simplest route), but that’s usually not advised here because it offers no personal asset protection. Most serious school founders incorporate it in some form. In fact, if you plan to seek accreditation and grants, incorporating as a non-profit educational institution is often beneficial for credibility and tax-exempt status (though you’ll have to follow non-profit compliance rules). To get started, you’ll typically register your chosen entity with the Secretary of State in the state where your university will be located. This process involves filing articles of incorporation (or organization, for an LLC), paying a fee, and registering the official name of your university. Ensure the name you choose isn’t already in use and contains words allowed by state law (some states regulate use of terms like “University” or “College” in business names). For instance, Maria might register “GreenTech Institute, Inc.” as the legal name if “university” requires special approval until she’s licensed. This step usually takes a few weeks for state approval, and once done, congratulations – you’ve laid the legal cornerstone of your future college!

3. Choosing Your State Wisely: Not all states are equal when it comes to opening a university. Each U.S. state has its own regulatory agency for higher education, and requirements (as well as costs) can vary dramatically. It pays to do thorough homework and pick a state that aligns with your plans. Consider factors like state regulations, taxes, fees, and even local demand for education. For example, states like Florida, Texas, or Arizona are often cited as business-friendly for new universities – they have no state income tax (in Florida and Texas), relatively lower regulatory hurdles, and cheaper real estate. On the other hand, a state like California has a high state income tax (8–10% additional on earnings) and an annual $800 business fee, plus stricter labor laws that could increase costs. If Maria’s GreenTech college were set up in California, she’d face higher taxes and would need to hire all staff as employees rather than contractors due to state law changes, which can be costlier. Meanwhile, if she chose Texas, she’d avoid income tax but discover Texas has a unique two-step approval for degree programs (requiring applications to two different agencies) – slightly more paperwork, but manageable. Another vital consideration: state licensing rules. Some states require new institutions to already have accreditation to get a license (a bit of a catch-22 for startups). In fact, 29 states don’t allow non-accredited universities to operate at all without prior accreditation. If you start in such a state, you’d need to partner with an accredited institution or get an exemption while you pursue accreditation. Other states, however, will grant an initial license to operate and give you a window (a few years) to become accredited. This is a big strategic factor – many new university founders choose states like Arizona or Florida partly because they provide a path to start teaching students first and earn accreditation within a given timeframe, rather than demanding it upfront. In summary, research state laws on higher education, consult their regulatory agencies, and possibly seek advice from an accreditation consultant or attorney to identify the optimal state for your university. Consider where your target student base is, too – opening a college in a state with growing population and few competitors could be advantageous, whereas saturations in some regions might pose challenges.

4. Registering the University Name: Once you’ve picked a state and set up your legal entity, you’ll formalize your university’s name and brand. Legally, as mentioned, the name is registered during business incorporation. But beyond that, you might need to register a “Doing Business As” (DBA) name if your corporate name is different from the public-facing name. For instance, Maria’s entity might be “GreenTech Education Corporation” but she wants to publicly call it “GreenTech University” – she may need a DBA if full university status isn’t immediate. Additionally, check if the state’s education department has rules on naming. Often, states protect terms like “University” or “College” to ensure only authorized institutions use them. In practical terms, choose a name that reflects your mission and is memorable. Once you have it, secure the domain name (website URL) for your college, and consider trademarking the name and logo to protect your brand. This early branding work sets the stage for marketing later on.

Before moving on, let’s recap with a mini story: Maria defined her mission (to create an eco-focused institute), chose a for-profit C-Corp structure to allow investors while still pursuing her educational goals, decided to open in Arizona for its friendly regulations and growing tech industry, and registered the name “GreenTech University” with the state. She’s now holding the approved incorporation papers – a thrilling milestone. The vision is no longer just in her head; it’s on official documents. Of course, a lot remains to be done – getting academic approval, hiring faculty, finding a campus or setting up online platforms. But by laying a solid foundation with clear vision and proper legal setup, the dream of opening a university moves into the realm of reality. Next, we’ll dive into the crucial aspects of accreditation, licensing, and regulations – essentially how to get the necessary approvals to offer degrees and ensure your university meets quality standards.

Accreditation, Licensing, and Regulations

Launching a university isn’t as simple as opening the doors and enrolling students – you must navigate a maze of accreditation, licensing, and regulatory requirements to ensure your institution is recognized and credible. These terms can be intimidating, so let’s break them down with straightforward explanations and a guiding scenario. Think of this process as earning a series of “gold stars” or badges for your new college: one from the state (license to operate) and one from independent reviewers (accreditation). Both are essential for gaining trust and legitimacy in higher education.

State Licensing Basics: Before a university can confer degrees or even call itself an accredited college, it needs permission from the state where it operates. This comes in the form of state authorization or licensure – essentially a charter that says “Yes, you are allowed to run a postsecondary educational institution here.” Each state has a higher education commission or agency that sets standards for granting this approval. The process usually starts with a detailed proposal or application. You’ll submit documents describing your university’s mission (which we crafted earlier), the programs you plan to offer, admission standards, facilities, and – very importantly – your financial projections and proof of stability. Think of it as writing a business plan for the state regulators, demonstrating that your college will meet educational needs and not collapse financially partway through. States want to protect students, so they scrutinize whether your plan is sustainable and in the public interest. For example, your application might need to show you have at least 2 years of operating funds in reserve (many states expect around $250,000 or more in readily available funds as a cushion). You may also need to detail curricula, faculty qualifications, and policies (like refund policies for students, governance structure, etc.).

Once the proposal is ready, you’ll file a formal application and pay licensing fees to the state. The fees and timeline vary – some states have modest fees and a quick review, others charge significant amounts and can take months or even a year to decide. A few states can indeed have quite stringent requirements; for instance, a state might mandate a site visit before approval, or like Texas, require multiple agency approvals for certain programs. Don’t let this discourage you. With careful preparation (and often with the help of experts), you can navigate it. It’s often recommended to consult a license and accreditation consultant at this stage. These consultants are professionals deeply familiar with each state’s rules and can guide you in preparing your application to meet all criteria. They act as translators, turning complex regulatory jargon into actionable to-do lists. For example, if a requirement says “provide audited financial statements,” and you’re not a finance person, a consultant will help you get those documents in order and explain them – ensuring you meet the criterion of financial stability. Many founders say this guidance is invaluable in avoiding mistakes that could delay approval.

One key tip: research exemptions. Some states have exemptions for certain types of institutions (like religious colleges or specialized training schools) which might simplify licensing. If by chance your model fits an exemption, you could fast-track with just an exemption letter rather than a full license (though most full universities won’t qualify for broad exemptions). Also, recall those 29 states requiring accreditation first – if you’re in one of those, your strategy might involve partnering with an already accredited institution to offer programs initially, or starting in another state and later expanding.

What is Accreditation? Now onto the second badge: accreditation. If state licensure is like getting a driver’s license (permission to drive), accreditation is like getting your car inspected and approved by a trusted mechanic – it signals quality and safety to everyone else on the road. In educational terms, accreditation is a voluntary, rigorous review process by an independent body that evaluates your university’s programs, faculty, facilities, and academic standards. When your college is accredited, it’s essentially awarded a “gold star” or seal of approval that tells students, employers, and the government that your institution meets established standards of quality. This stamp of legitimacy is crucial. Without it, students might be wary of enrolling, other colleges won’t accept your transfer credits, and critically, students can’t access federal financial aid like loans and grants at your school. In fact, many states require you to achieve accreditation within a few years of opening or they’ll revoke your license.

There are different types of accreditation in the U.S.:

- Regional Accreditation: Considered the gold standard, six regional accreditors cover different parts of the country (for example, Middle States, Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, etc.). These accredit most non-profit and state institutions. Regional accreditation is highly respected and often more stringent, but the process can be longer (typically 3-5 years for new schools).

- National Accreditation: These accreditors aren’t tied to geography but often to types of schools (like career colleges, online universities, or faith-based institutions). National accreditation is generally a bit quicker and less costly to obtain than regional – sometimes achievable in 2-3 years – but it may be less recognized in certain academia circles. Still, it’s a valid path, especially for specialized or for-profit institutions.

- Programmatic Accreditation: This is an additional accreditation for specific programs (like nursing, engineering, business schools, etc.) by specialized agencies. You usually pursue these after getting your institutional accreditation (regional or national), to certify that individual programs meet industry standards. For example, you might get your MBA program accredited by a business accreditation body once your university as a whole is accredited.

Working with an Accreditation Consultant: If the accreditation process sounds daunting, remember you’re not alone. Just as you’d hire an architect to build a complex house, you can hire an accreditation consultant to guide your university through the accreditation journey. This person or team specializes in understanding accrediting bodies’ requirements – from documenting your curriculum and faculty credentials to preparing for site visits by the accrediting team. As mentioned earlier, they are like specialists who help you navigate the labyrinth and earn that gold star. For a hypothetical example, imagine you have to prepare a self-study report for the accreditor (which is often a massive document analyzing every aspect of your institution). An accreditation consultant would help organize this effort, ensuring you address every standard in the accreditor’s handbook. They might conduct a mock audit of your school to catch any weaknesses before the real evaluators come. Essentially, they increase your chances of success on the first try – which is important, because delays in accreditation can strain your finances and reputation.

An accreditation consultant can also advise whether to pursue regional or national accreditation first, based on your university’s profile, and how to schedule things so you meet any state-imposed deadlines. Remember, many states give new universities about 3-5 years to become accredited after starting. That might sound like a long time, but the accreditation process itself can take several years, so you’ll want to get started as soon as you have your state license. A consultant will likely recommend you contact an accrediting agency early, possibly even before you enroll students, to understand their candidacy process. You typically become a “candidate” or “pre-accredited” institution first, which can take 1-2 years, and then progress to full accreditation.

Navigating Regulations and Keeping Compliant: Beyond licensing and accreditation, there are various regulations to follow at state and federal levels. For instance, if you plan to offer federal financial aid to students, your university will need to adhere to U.S. Department of Education regulations (and accreditation is a prerequisite for that). States might have specific consumer protection rules – like how you must handle student complaints or maintain student records. You will also need to ensure any professional programs (nursing, teaching, law, etc.) meet the regulatory requirements of those professions. As an example, if Maria’s GreenTech University wants to eventually offer a teacher education program, she’d need state approval from the education board in addition to general licensing. Or if offering nursing, the state nursing board must bless the program. These are additional hoops but necessary for your graduates to be licensed in their fields.

Don’t be overwhelmed: take it step by step. Focus first on state authorization, then on accreditation, while always keeping an eye on compliance with all applicable rules. Build a relationship with the regulators – yes, it’s okay to call the state agency and ask questions or clarify things; many are quite helpful to new institutions. And maintain open communication with your chosen accreditor; they often provide workshops or guidelines for new institutions.

To illustrate with a friendly hypothetical: think of the regulatory process like opening a restaurant. You need a business permit (state license), you want a good review from the food critic (accreditation), and you have health and safety codes to follow consistently (ongoing regulations). If you plan well, get expert help, and pay attention to the rules, you’ll pass inspections with flying colors and proudly display that health grade “A” in your window – or in our case, an accreditation certificate on your wall. It may require patience (accreditation especially can feel slow, requiring 2-4 years of demonstrating outcomes and improvements), but it’s absolutely doable. In fact, most new universities begin unaccredited but achieve accreditation within a few years by diligently following a roadmap.

In summary, accreditation and licensing are about building credibility and trust. They show that your university isn’t a fly-by-night operation, but a serious institution meeting high standards. By working with consultants and understanding the rules early on, you set yourself up for success. Next, we’ll delve into a question on many minds: the price tag. How much does it actually cost to open a university? Spoiler: it can be significant, but we’ll break down the costs and even discuss budgets for different scenarios (online vs. campus-based) to give you a clear picture.

How Much Does It Cost to Open a University?

One of the biggest questions aspiring founders ask is “how much does it cost to open a university?” The answer varies widely based on your university’s size, location, and model (for example, an online university will have a very different cost structure than a traditional campus). In this section, we’ll offer a breakdown of typical startup costs – from campus facilities to faculty salaries – and provide sample budget ranges for different scenarios. Think of this as building a financial blueprint for your dream college. It might seem daunting, but a clear understanding of costs will help you plan, fundraise, and make smart decisions from day one.

1. Campus vs. Online: Infrastructure Costs – One major factor in cost is whether you plan a physical campus, an online university, or a hybrid of the two. A campus-based university will incur substantial expenses for physical facilities. You’ll need to lease or purchase property for classrooms, offices, labs, dormitories (if residential), libraries, etc. The cost here varies by location. In areas with cheaper real estate (say, parts of the Midwest or states like Arizona or Florida), you might lease a suitable building for perhaps $5,000 to $10,000 per month. In contrast, prime areas like California or New York could easily cost $20,000+ per month for a modest campus space. If you aim big – constructing new buildings – expect several million dollars in construction and renovation costs. Even converting an existing office building into an academic facility (adding labs, wiring for tech, installing classroom equipment) can run into hundreds of thousands of dollars. On top of monthly rent or mortgage, budget for renovations, furniture, and safety compliance (like fire alarms, accessibility features).

For an online university or largely online programs, you can dramatically cut facility costs. You might only need a small administrative office or co-working space. Many online institutions start by renting a shared office for $500–$1,000 a month just for a mailing address and a place to keep records. Instead of physical classrooms, your “campus” is virtual – which means investing in technology (we’ll cover that soon) but not brick-and-mortar buildings. Some hybrid models use leased classrooms in office parks or partnership with existing schools for occasional in-person sessions to save cost. The campus vs. online decision is crucial for your budget. If funds are limited, starting online can lower initial costs, but remember that purely online universities still face significant spending on platforms and marketing to reach students across the globe.

2. Faculty and Staff – The Human Capital: Education is a people-centric enterprise. One of your largest ongoing expenses will be salaries for faculty and staff. To provide quality programs, you need qualified professors, instructors, and administrators. Let’s break this down:

- Faculty (Professors/Instructors): Depending on your course offerings, you might hire a mix of full-time faculty and adjunct (part-time) instructors. Adjunct faculty are typically paid per course taught; an adjunct might earn anywhere from $2,000 to $10,000 per course taught, depending on the field and your university’s pay scale. They’re often cheaper upfront since they don’t usually get benefits. Full-time faculty (with roles in teaching and research) come with higher salaries – often ranging from $60,000 up to $200,000 annually for senior or specialized professors. For example, hiring a Ph.D. professor in engineering could cost $100k+ a year, whereas a new instructor in English might be around $60k. Remember to account for employee benefits – health insurance, retirement contributions, etc. Benefits usually add about 20-30% on top of salaries. So a $100k salary might really cost you $120k–$130k with benefits.

- Administrative Staff: You’ll need people to handle admissions, student advising, registrar duties (keeping academic records), financial aid (especially if you plan to offer federal aid later), IT support, marketing, and so on. In a tiny startup college, some people wear multiple hats at first (for instance, one person might serve as both admissions counselor and registrar). But as you grow, you’ll need dedicated roles. Administrative staff salaries can range widely: perhaps $40,000 for a junior admissions coordinator, up to $150,000 for an experienced Chief Financial Officer or Provost. Many mid-level roles (student services manager, IT director, etc.) might fall in the $50k–$80k range. Plan for these because running a university is like running a small city – you need various departments functioning.

- Leadership: Don’t forget to budget for top leadership like a President or CEO of the university, academic deans, and a director of operations. In the beginning, you (the founder) might take one of these roles, potentially drawing little to no salary until students enroll. But accreditation standards will eventually expect that key positions are filled with qualified individuals. For budgeting, a President might be paid similar to a senior professor or more, depending on scale.

Sample Staffing Budget: Suppose you start a small college with 5 full-time faculty (avg $70k each), 10 adjuncts teaching a few courses (maybe $5k per course on average, each doing 2 courses per term = ~$10k each per term), and 8 staff members (averaging $50k each). Roughly, full-time faculty = $350k, adjuncts per term = $100k (if two terms, $200k/year), staff = $400k. That’s about $950k in salaries, and adding 25% benefits brings it to around $1.2 million per year. This is just illustrative – your numbers could be lower with more adjuncts and fewer full-timers, or higher if you scale up quickly. The key is to align hiring with enrollment growth; you don’t want more staff than students. Many new universities start lean – leveraging adjuncts, and having small teams, then scale hiring as tuition revenue grows.

3. Technology Infrastructure: Today’s students expect seamless technology, whether classes are online or on-campus. You’ll need to invest in a Learning Management System (LMS) – basically an online platform where you can host course materials, assignments, and enable interactions. You have options to build or buy:

- Developing a custom LMS could cost anywhere from $25,000 to $100,000+ to create, plus ongoing maintenance. This route gives you control to tailor features, but it’s expensive upfront.

- Using a ready-made LMS (like Canvas, Blackboard, or open-source Moodle) usually involves a subscription fee. Some cloud LMS providers charge roughly $5 per student per month. So if you have 200 students, that’s $1,000/month. This can be cost-effective to start, though costs grow with the student population. Many small colleges opt for such solutions to avoid heavy dev costs and get a reliable system from day one.

Beyond the LMS, consider other tech needs:

- Student Information System (SIS): A database for student records, enrollment, grades, etc. Sometimes an SIS is integrated with the LMS or can be a module in it. There are SaaS (Software as a Service) SIS options that might cost a few thousand per year.

- Computer Labs and Hardware: If on campus, you’ll need computer labs or at least some computers for student use, projectors, smart boards in classrooms, etc. Outfitting a single smart classroom can easily cost $10k (for a projector, sound system, etc.). A lab with 30 computers could be $30k+. Networking hardware (routers, servers if self-hosting anything) adds to this. Let’s estimate maybe $50,000 to $200,000 in various tech equipment for a small campus launch, depending on how many rooms and labs you have.

- Software and Licenses: This includes not just teaching software, but also office productivity tools, possibly library database subscriptions (more on library in a moment), and specialized software for programs (e.g., design software for an art program, statistical packages for research, etc.). Allocate maybe tens of thousands here as well, depending on specialization.

- Student Information System (SIS): A database for student records, enrollment, grades, etc. Sometimes an SIS is integrated with the LMS or can be a module in it. There are SaaS (Software as a Service) SIS options that might cost a few thousand per year.

4. Library and Learning Resources: A university needs to provide learning resources – traditionally, a library full of books and journals. Nowadays, much of this is digital. Still, you should plan for a combination of physical and digital resources:

- Setting up a basic physical library collection might cost anywhere from $50,000 to $100,000 initially for a small college, purchasing key books and materials. Larger or more specialized collections can run into the millions over time, but you can start modest and build up.

- Digital resources are crucial: online academic journals, research databases (like JSTOR, EBSCO, etc.), and e-books. These often come as subscriptions. For instance, access to a bundle of academic journals might cost several thousand dollars per year, scaling with the number of users. A comprehensive database package could be $20k per year or more for a small institution.

- To save costs, many new institutions join library consortia or networks, which allow sharing resources between member libraries and group negotiation for better prices. This might involve a membership fee but can significantly broaden what you can offer your students. Another strategy is forming partnerships with local libraries or larger universities for library access privileges.

- Don’t forget infrastructure for the library: if physical, you need space, shelves, catalog systems; if digital, you need a good online portal where students can find resources (often provided by library management software).

5. Marketing and Student Recruitment: “If you build it, they will come” does not automatically apply to universities. You must actively recruit students, especially as a new, unknown institution. Marketing will be a significant early expense to reach your first cohorts. This includes:

- Website Development: A professional, user-friendly website is absolutely essential – it’s the front door through which prospective students will walk. Budget maybe $10,000 to $50,000 for an initial website design and build. If you have in-house talent this could be less, but often hiring a web design firm experienced in higher ed is worth it. Make sure the site can handle applications, showcase programs, and perhaps even host online classes if needed.

- Digital Marketing (SEO and Ads): You want your university to appear in Google searches for terms like “opening a university program in [your field]” or “colleges in [your area]”. Search Engine Optimization (SEO) is a practice to optimize your site and content so you rank higher on search queries. This is often a slow, organic process (writing blogs, getting other sites to link to you, etc.), but you might hire an SEO specialist or agency to help – cost could be a few hundred to a couple thousand dollars a month. Pay-Per-Click (PPC) advertising (like Google Ads or Facebook Ads targeting potential students) can get quicker attention. This might cost anywhere from a few hundred to several thousand dollars per month depending on how aggressively you advertise and the competitiveness of the market. For example, bidding on keywords like “online MBA degree” can be expensive since many universities compete for those. You can set a budget cap, say $1,000/month, to control spend. Social media marketing is also key – perhaps not huge dollars, but some for content creation or sponsored posts.

- Traditional Marketing: Though much happens online, you might still invest in traditional methods. Printing brochures, attending college fairs, local radio or newspaper ads, even billboards – these can add up. A small college could spend maybe $20,000 in various print materials and events initially. Larger campaigns (billboards, TV) can run into the tens or hundreds of thousands. Many new universities rely more on digital and word-of-mouth at first due to cost.

- Recruitment Personnel: Having dedicated admissions counselors or recruiters is important. They might travel to high schools, speak at events, follow up with inquiries, and guide applicants. As noted earlier, a recruiter’s salary might be in the $40k–$80k range. Even if you start with one or two, that’s part of the budget. They may also need travel and outreach budget (to visit schools or community colleges for transfer recruitment, for example).

- Building Trust: Marketing isn’t just ads – it’s building credibility. Early on, you might do things like host free workshops or webinars to get your name out, or form partnerships with local employers or community organizations. These efforts may not be huge line-item costs but require time and maybe some funds for events. It’s wise to highlight any accreditation progress or approvals in marketing to build trust (“Licensed by the State of X” or “Faculty with degrees from prestigious universities,” etc.). We’ll talk more about enrollment strategy in the next section.

To give a sample budget range, let’s outline two scenarios:

- Scenario A: Small Online University Launch: You rent a small office ($1k/month). Technology is your main infrastructure cost – say $50k initial for a website, LMS setup, and some computers. You hire mostly adjuncts and a few full-time faculty for oversight, maybe totaling $500k in the first year (assuming you start with a few hundred students). Admin staff small, say $200k. Marketing you invest $100k in the first year to attract those students (website, digital ads, etc.). All together, maybe you’re looking at around $1 million to start and run the first year. Keep in mind, if you have, for instance, 200 students paying $5,000 tuition each, that’s $1 million revenue, which could cover it – these are the kind of numbers to play with for viability.

- Scenario B: Mid-Sized Campus-Based College: You lease a campus building for $10k/month ($120k year). Spend $500k renovating and equipping it. Faculty and staff for a broader program offering: $1.5 million/year. Technology and library: $300k initial (labs, network, library setup). Marketing: $200k to make a regional splash and recruit first class. This scenario might be $2 to $3 million needed upfront and for the first year of operations. You’d likely aim to enroll a larger number of students or have substantial fundraising to cover this. Maybe you start with 500 students at $10k tuition = $5 million revenue, which covers costs and leaves room to grow. But reaching 500 students as a brand-new college might take a few years, so initial capital would bridge the gap.

6. Sample Startup Budgets: You might wonder what an actual startup budget looks like for a new university. Let’s outline a simplified version:

- Initial Setup Costs (Pre-launch): State licensing fees (could be $5k–$50k depending on state), Accreditation application fees (maybe $5k initial), Legal fees for setup (lawyers, etc., perhaps $20k), Consultants (licensing/accreditation consultant might charge, say, $20k for a basic package up to $100k for extensive help; you could start with minimal consulting and ramp up). Facility deposit or down payment if buying property. Website and branding (logos, marketing materials) $30k. Pre-opening hiring (maybe you hire a Director or key personnel 6 months before launch to prepare). Let’s ballpark perhaps $200k–$500k in pre-launch expenses before you even open doors, especially if you include an initial facility cost and regulatory fees.

- Operating Costs (Year 1): Faculty & Staff salaries (as computed in scenarios above), facility lease, utilities (don’t forget power, internet, insurance on property ~ these might add tens of thousands), marketing, academic supplies (labs, if any consumables or equipment maintenance), student services (maybe you set aside funds for tutoring or career services materials), and miscellaneous (from office supplies to graduation event costs – yes, think ahead to that first graduation!). A lean small college might operate year 1 on say $800k–$1.5M, a larger one might need $3M–$5M or more.

It’s wise to have a contingency or emergency fund as well – things can cost more than expected or enrollment might ramp up slower. That’s why states often require that proof of $250k or more reserved – it’s a buffer so you don’t fold at the first hurdle.

7. Funding the Dream: With these numbers, it’s clear opening a university is a serious financial endeavor. How do people fund it? Many use a combination of personal investment, loans, and investors or donors. If you’re positioning as a non-profit, you might raise funds via philanthropy (though new colleges without a track record might find it hard to get big donors initially). If for-profit, you may attract investors who see long-term revenue potential (education can eventually be profitable once enrollment grows). In some cases, entrepreneurs buy an existing struggling college rather than start from scratch (that can sometimes be cheaper and come with accreditation, but that’s another strategy altogether). There are also some grants for educational institutions, but those usually require non-profit status and often come after you’ve somewhat established (e.g., federal grants for specific programs, etc., which you can’t count on from day one).

A quick story to tie this together: Let’s say two friends, John and Lisa, decide to open a new private college focusing on coding and tech skills. They choose to rent an old training center building in Texas. They spend about $100k outfitting it with modern computer labs. They hire industry experts as adjunct instructors to keep faculty costs low initially, and just 3 full-time faculty to design curriculum. Their first-year budget is around $1 million. To fund this, John uses savings and a small business loan to gather $300k, and Lisa brings an angel investor who puts in $500k because he believes in the project. They also get $200k in commitments from a local tech company for sponsoring a lab (in exchange, the lab is named after the company). With $1 million in hand, they proceed, and aim to enroll 150 students paying ~$7k each in the first year (which would roughly break even). They’re prepared that if only 100 show up, they have enough buffer to operate and ramp up marketing. This scenario underscores the kind of planning and resourcefulness needed. Opening a university is a big investment, but by knowing the numbers and planning for various outcomes, you can increase your chances of financial sustainability.

In conclusion for this section, while the cost to open a university can be high, it’s important to view it as building a long-term enterprise. Upfront costs are significant, but a successful university will operate for decades or centuries, educating thousands of students. By carefully budgeting for facilities, people, technology, and marketing, you set the stage for a venture that is both impactful and economically viable. And remember, resources like consultants and financial model templates (some guides even provide profit & loss spreadsheets for university startups) can help you refine your cost estimates. Next, we’ll discuss the heart of the university: academics and student services – how to design programs that attract students and support them to success.

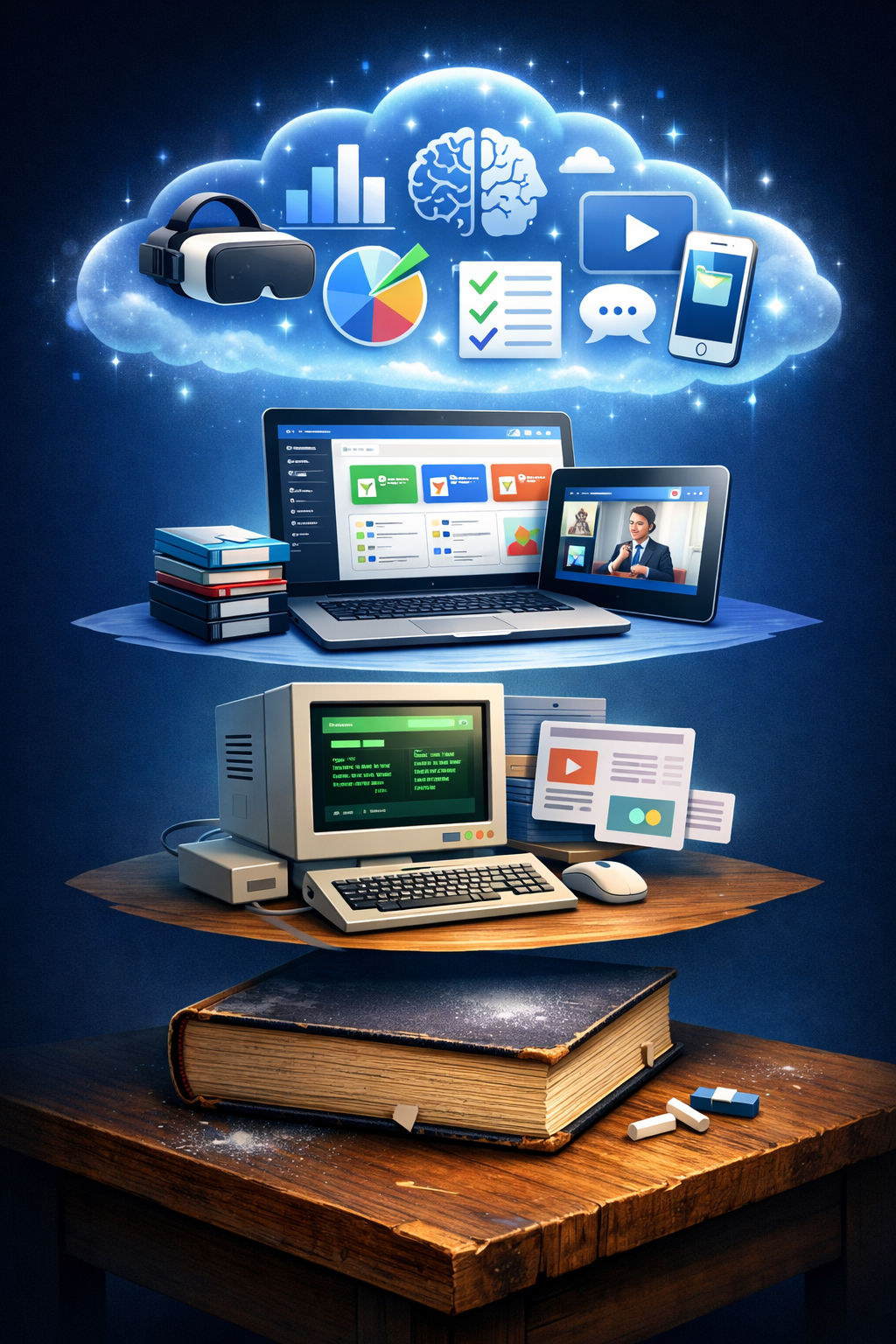

A modern university campus building, representing the significant infrastructure investments required when opening a new college. Physical facilities involve costs for leasing or purchasing property and equipping learning spaces, though online universities can start with minimal brick-and-mortar commitments.

Curriculum, Programs, and Student Services

Designing a strong academic offering and supporting your students are at the core of any university’s mission. In this section, we’ll explore how to develop compelling curriculum and programs that meet student and industry demand, and why robust student services are essential for retention and success. Think of it this way: the previous sections covered building the ship (licensing, funding, infrastructure). Now we focus on the voyage itself – what learning experiences you provide and how you care for your passengers (students) on their journey.

Building Your Academic Programs: A new university has a blank slate to create programs, which is exciting but also a big responsibility. You want programs that are both aligned with your mission and attractive to students (and by extension, employers who will hire graduates). A smart strategy is to start with a focused set of programs that are in high demand and relatively straightforward to launch. For example, many new institutions begin with programs in business, technology, or healthcare, as these fields consistently attract students and meet clear workforce needs. These programs also tend to have well-defined curricula and aren’t subject to external professional licensure requirements (with the exception of some healthcare fields). Contrast that with, say, a law or medical school – those require significant additional accreditation and infrastructure (e.g., law libraries, medical labs) and might be too complex for a Phase 1 launch. You can add such specialized programs later once you have a foundation.

When crafting curricula, research industry and academic standards. You don’t have to reinvent the wheel – look at established universities’ program outlines for inspiration, and consult advisory committees from relevant industries. For instance, if you’re creating a cybersecurity degree, meet with cybersecurity professionals about what skills and certifications graduates should have. Ensure your program learning outcomes match what employers want. Also, consider regulatory factors: some states might require that certain programs meet credit-hour minimums (e.g., a Bachelor’s must be 120 credit hours). An accreditation consultant can help ensure your curriculum designs meet the expectations of accreditors and state rules.

Keep the curriculum student-centered and flexible if possible. Many modern learners appreciate options like evening/weekend classes or online components (even if you’re campus-based, hybrid flexibility can widen your appeal). Also, plan for assessment and continuous improvement: you’ll need a system to regularly review how well courses and programs are achieving their outcomes and make adjustments (accreditors will expect this). That can be as simple as faculty meetings to review student performance data and as formal as an assessment office tracking metrics.

Hypothetical example: Suppose our GreenTech University from earlier is starting with three programs: a B.S. in Environmental Science, a B.A. in Sustainability Management, and an M.S. in Renewable Energy Engineering. To design these, the founders gathered a team of academic experts – maybe some retired professors or industry experts – to outline courses. They ensure the Environmental Science degree has a strong core in biology, chemistry, and field research, since that’s standard for the field. They include some unique electives on climate technology to stand out. For Sustainability Management, they integrate business courses with environmental policy courses, to make grads versatile. And for the engineering master’s, they align it with current trends in solar and wind tech, perhaps seeking advice from a partner energy company. By aligning with what’s relevant and needed, these programs are more likely to attract students.

Hiring Qualified Faculty: As part of program development, you need to line up faculty who can deliver the curriculum. Accrediting bodies will look at faculty credentials – typically, for a bachelor’s program, instructors should have at least a master’s in the field (and often a good portion with doctorates); for master’s programs, you want PhD or terminal degree holders teaching core courses. Experience matters too. You might mix seasoned academics with industry practitioners (especially in applied fields). That can give students a richer experience and also helps with marketing (“learn from professors who’ve worked in the field”). Provide support for faculty to develop courses, especially if you’re doing anything innovative like project-based learning or online teaching – maybe offer training workshops or templates.

Student Services – Supporting Success: Now let’s turn to the other half of this section: student services. Academics alone don’t guarantee student success; the support services you offer can make or break a student’s experience. What do we mean by student services? It includes things like:

- Academic Advising: helping students pick courses, stay on track to graduate, and troubleshoot academic challenges.

- Tutoring and Writing Centers: resources for extra help in difficult subjects or to improve skills.

- Career Services: assisting students with resume writing, interview practice, job fairs, and connecting them to internship opportunities.

- Counseling and Mental Health Services: providing support for students’ well-being. College can be stressful, and having counselors or at least referrals available is important (many campuses partner with external counseling services if they can’t hire full-time counselors initially).

- Financial Aid Advising: even if initially you don’t have federal aid, students will have questions about paying for college, scholarships, etc. Helping them navigate this builds trust.

- Student Life and Engagement: even a non-residential college benefits from having clubs, activities, or online forums where students can form community. This might be student government, interest clubs (like a coding club or environmental club), or organizing workshops and events (even virtual ones).

- Disability Services: ensuring accommodations for students with disabilities (like extra time on tests, accessible facilities) is not only often legally required but a key part of being inclusive.

Why invest in these services? Because they directly impact student success and satisfaction. Studies have shown that robust student support services lead to higher retention and graduation rates. When students feel supported – academically, professionally, personally – they are more likely to persevere and complete their degree. From a business perspective, higher retention means students stay and continue paying tuition, and happy graduates become your alumni network who can refer others. But more importantly, from an educational mission viewpoint, these services ensure you’re truly helping students benefit from their education. Americans broadly agree that colleges should provide such support to help students succeed.

Even if you start small, put some basic services in place. For example, designate a staff member or faculty to act as the go-to academic advisor for freshmen. Create an “early alert” system – if a student is failing a class, have someone reach out to check in or offer tutoring. For career services, maybe you can’t have a full office yet, but you can host a monthly career workshop and invite local professionals to mentor students. Little steps like that go a long way.

Hypothetical scenario: It’s year 2 at GreenTech University. They have 200 students now. One student, Jamal, is struggling in the advanced math required for the Renewable Energy Engineering program. Because GTU set up a small tutoring center (just a room with some top senior students as peer tutors), Jamal gets help twice a week and improves his grades. Meanwhile, another student, Priya, is nearing graduation; the career counselor (who is also the admissions director wearing two hats) helps her polish her resume and connects her with an internship at a solar firm through an alumni contact. Priya lands a job before graduation. These wins, though anecdotal, reflect in statistics – GTU boasts an 85% first-to-second-year retention rate and growing job placement figures. When they promote these in marketing, it builds credibility and word-of-mouth.

Feedback and Improvement: Integrate feedback loops. Survey your students about their satisfaction with courses and services. Maybe they want longer library hours or an online portal for advising – student input can guide where to invest in services as you grow. Also, as regulations, Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) compliance, Title IX (gender equity and handling of any harassment issues) – ensure you have policies and at least minimal services in place to comply with these. It could be as simple as contracting a counselor on an as-needed basis to handle any serious issues, or having a part-time Title IX coordinator. These aren’t just legal checkboxes; they foster a safe and supportive campus environment.

Continuous Curriculum Enhancement: On the curriculum side, plan for growth. After initial programs succeed, you’ll likely add more programs (we’ll discuss expansion in the next section on long-term growth). But even within current programs, keep them updated. Maybe each program has an advisory board of industry folks who meet annually to suggest improvements. For example, your tech program might need a new course on artificial intelligence after a couple years, as the field evolves. Being responsive keeps your offerings relevant and appealing.

In summary, curriculum and student services are two pillars that uphold educational quality. A well-thought-out curriculum attracts students and meets their learning needs; robust student support ensures they can thrive and achieve their goals. By focusing on high-demand programs, hiring great educators, and creating a supportive learning environment (both in and out of the classroom), your new university will build a reputation for academic excellence and caring community. This not only helps with accreditation and outcomes but also becomes a selling point in recruitment – students want to attend a school where they feel they’ll be guided and valued.

As we move on, the next logical topic is how to actually get those students in the door. We’ve built the programs and support systems; now let’s talk about marketing and enrollment strategy – how to convince students (and their parents, in many cases) to trust a brand-new university and join as pioneers in your educational venture.

Marketing and Enrollment Strategy

You’ve set up the university, developed programs, and ensured support services – now you need students! Crafting a smart marketing and enrollment strategy is key to getting your first class in the door and building momentum for growth. Marketing a new university might seem daunting (no alumni to sing praises yet, no rankings, an unknown brand), but with the right approach, you can attract students by highlighting your strengths, building trust, and meeting your audience where they are. In this section, we’ll guide you on how to build credibility from scratch, use modern marketing tools like SEO and digital ads, and successfully enroll those crucial first students.

Building Trust from the Ground Up: One of the biggest hurdles for a new institution is credibility. Prospective students (and their families) might wonder, “Is this a real, quality school? Will my degree be respected?” To address this, make trust-building the centerpiece of your marketing. Here’s how:

- Highlight Accreditation and Approvals: Even if you are initially operating under a provisional license, be transparent about your status and milestones. For example, “Licensed by the State of X to grant degrees” is a reassuring statement you should display on your website. As you work toward accreditation, mention partnerships or candidacy status: e.g., “An applicant for accreditation with Y Commission” if applicable. Once you get any programmatic accreditation or special recognition, celebrate it in press releases and on the homepage. These signals show external validation of your quality.

- Showcase Your Team and Partners: Introduce your faculty, advisors, and founders with their qualifications. If you have professors from well-known universities or industry veterans, that immediately boosts credibility. Also mention any partnerships – perhaps you have an internship program with a reputable company, or an academic partnership for library resources. Seeing recognizable names and faces can assure prospects that your university is legitimate and backed by expertise.

- Student Success Stories (even hypothetical initial ones): In the very beginning, you won’t have graduates yet, but you can perhaps pilot some short courses or certificate programs and get testimonials. Or feature profiles of your inaugural students (“Meet Jane, one of the first students at Our College, pursuing her dream in XYZ”). Authentic stories and reviews will become powerful as soon as you have them. Encourage word-of-mouth: often your first cohort might include local students who heard about it from an info session or a personal referral. Treat them like gold – their positive experience and subsequent recommendation will help recruit the next cohort.

Digital Marketing – SEO and Online Presence: In today’s world, students actively search online for education options. So, invest in a strong online presence:

- Website & SEO: Ensure your website is optimized for search engines. Use the keywords naturally in your site content that students might search, such as “how to open a university degree program” (maybe not that one specifically – that’s our guide’s title! – but terms like “business degree in [your city]” or “[field] program flexible schedule”). If your target demographic includes working adults, have content about “earn your degree while working” etc. If you have unique offerings, write blog posts about them to draw traffic. Search Engine Optimization can be technical, but a basic principle is to have relevant, quality content and get other sites linking to you. Perhaps write guest articles or get local news to cover the launch of your university (local press coverage not only spreads the word, but the backlinks also help SEO).

- Social Media: Establish profiles on platforms popular with your audience – likely Facebook for community presence, Instagram for visual campus life snippets, LinkedIn for professional credibility (especially if you have grad programs or working adult students), and possibly TikTok or YouTube if targeting younger undergrads with creative content. Post regularly: showcase campus progress (“Construction of our new lab is complete!” with photos), student life (“Orientation day fun!”), academic insights (short videos of a professor explaining a cool concept). Social media can humanize your brand and build a following. You can also run targeted ads on these platforms – e.g., an Instagram ad saying “Now enrolling: XYZ University – Launch your career in Renewable Energy. Apply by Aug 1!” aimed at users aged 18-30 interested in sustainability, within 50 miles of your city.

- Pay-Per-Click (PPC) Ads: Running Google Ads for relevant search terms can put you on the radar quickly. For a new college, you might bid on terms like “[Your City] colleges” or “[Your specialization] degree online.” Set a budget and monitor results. Over time, as SEO improves, you may rely less on paid search, but initially it can generate leads. Also consider retargeting ads – those are the ones that follow users who visited your site, reminding them to come back and apply.

- Content Marketing: Publishing valuable content (like guides, infographics, short courses) can attract prospective students. For instance, if you open a coding bootcamp as part of your offerings, you might publish a “Beginner’s Guide to Python” e-book – people download it, and in exchange you get their email to follow up about your programs. This establishes you as an authority and keeps potential applicants engaged.

Enrollment Tactics – From Interest to Application to Enrollment: Marketing generates interest, but you also need an effective admissions process to convert that interest into actual enrolled students.

- Personalized Outreach: Especially as a small new university, you can offer a high-touch admissions experience. Follow up each inquiry with a personal email or phone call. For example, if a student requests info on your website, have an admissions counselor reach out to ask if they have questions and maybe set up a campus tour (or virtual tour). People appreciate feeling seen and helped rather than just getting form letters.

- Admissions Funnel: Set up a clear path: Inquiry -> Application -> Acceptance -> Enrollment. At each stage, provide the information and encouragement needed. For instance, have clear application instructions and a friendly portal. Once someone applies, respond quickly (one advantage of being new/small is you’re not dealing with tens of thousands of apps, so you can turn decisions around fast and communicate often). When you accept a student, celebrate it – send an acceptance package (physical mail or a creative email) that builds excitement. Then guide them to the next steps (financial aid, course registration, orientation).

- Incentives for First Students: To entice initial enrollment, consider some incentives. This could be scholarships (“Founders Scholarship: 50% off tuition for the first 50 students!”) or other perks like locked-in tuition rates (no increase for four years), or extra mentoring opportunities. Early adopters know they’re taking a bit more risk on a new school, so rewarding them is fair and wise. Just be transparent and ensure you can afford any discounts offered (factor them in your budget).

- Leverage Your Niche: If your university has a particular niche or innovative approach, make sure that’s front and center in recruitment. For example: “Be part of an exclusive small college experience focused on personalized learning” or “Join the only program in the region specializing in [X]”. Students who resonate with that unique value proposition are more likely to apply, even if you’re not famous. It’s often better to appeal strongly to a specific audience than to vaguely try to be everything for everyone as an unknown entrant.

- Community and Grassroots Outreach: Don’t underestimate local recruitment strategies. Hold informational workshops at community centers or libraries. Visit high schools or community colleges if you have transfer programs. Engage with local employers – perhaps they’ll refer their employees for your new evening MBA. Being present in the community builds word-of-mouth. If you can get a few local champions (educators, community leaders) excited about your mission, they’ll spread the word. For example, a local guidance counselor might encourage students to consider your college if they know you personally and trust what you’re offering.

Manage and Refine: Marketing and enrollment is not a one-and-done effort; track what works and refine. Use analytics – which web pages get the most visits, which ads lead to inquiries, where do inquiries drop off in the funnel, etc. Maybe you find a lot of people start an application but don’t finish; that’s a signal to perhaps simplify your application or send friendly reminders (“Need help finishing your application? We’re here for you.”). Or you might see a certain program has high interest but low enrollment; maybe the tuition is too high for that audience or they need more info about career outcomes – adjust your messaging accordingly.

The First Cohort – Mission Accomplished: Let’s illustrate success: After months of marketing, suppose your target was 100 students for the first fall. By August, you have 120 acceptances and 90 have confirmed enrollment. It’s a bit short, but you anticipated this scenario. Instead of panicking, you double down on communication with undecided students and maybe extend the application deadline for a few more latecomers. You host a “Q&A with the founders” webinar for all accepted students to personally welcome them and answer any last-minute questions (some had been on the fence; this personal touch convinces them to join). You also roll out a referral bonus: any enrolled student who refers a friend that enrolls gets a $500 bookstore credit. A few students bring in their friends. Come the start of term, you have 100 students – goal met! They form the tight-knit inaugural class, and you make sure to give them a fantastic experience because they will be your evangelists.

Marketing a new university requires creativity, persistence, and authenticity. Authenticity is worth emphasizing: be genuine about what your institution offers and stands for. In the age of online reviews and social media, honesty goes a long way. If something is still in progress (like a facility or accreditation), communicate what you’re doing to address it rather than hiding it. Students appreciate being part of a developing story if you make them partners in the journey (“you can help us shape traditions at this new college!” is a positive spin).

To wrap up this section, remember that enrollment growth often starts slow and accelerates as reputation builds. Don’t be discouraged if the first year is small; focus on making those students successful and happy. Their success stories and your proven track record will make marketing each subsequent year easier. By using targeted digital strategies and fostering trust through transparency and engagement, you’ll gradually shed the “newcomer” status and develop a brand that stands on its own. In the next section, we’ll discuss how to sustain and grow your university over the long term – turning that initial momentum into lasting success and resilience (which circles back to our recession-proof theme in new ways as the institution matures).

Long-Term Growth and Sustainability

Congratulations – let’s fast-forward a bit and imagine your private university is up and running. The first students have graduated, you’ve overcome initial challenges, and you’re looking toward the future. How do you ensure long-term growth and sustainability so that your university not only survives but thrives for decades to come? In this final section, we’ll cover strategies for steadily growing your programs and impact, achieving and maintaining accreditation, and building financial resilience (even more important as you scale). Long-term thinking is crucial because a university, more than many businesses, is built to last and create a legacy.

Accreditation Milestones and Renewal: Earlier, we discussed initial accreditation, which is a huge milestone for a new university. In the long term, you’ll go through accreditation renewal cycles (most accrediting bodies reevaluate institutions every 5-10 years). It’s important to integrate a culture of continuous improvement so that accreditation isn’t a one-time hurdle but an ongoing process. That means regularly assessing student learning, getting feedback, updating curricula, and documenting all of this. Many successful universities have a small institutional research or effectiveness office that constantly compiles data and reports on key metrics (like graduation rates, job placement, student satisfaction). This not only keeps you accreditation-ready, it actually helps you identify areas to improve proactively. Also, as you add programs or even new degree levels (say you start offering a Master’s when you were only Bachelor’s), be aware of substantive change approvals – accreditors often require you to get approval for major changes or additions. Plan ahead for those timelines (for instance, adding a graduate program might require a committee review and site visit).

One advice: work closely with your accreditor and possibly an accreditation consultant even long-term. They can alert you to changing standards. For example, perhaps accreditors shift focus to student outcomes like loan default rates or graduate salaries – you want to be ahead of that and have strategies to support student success in those areas. Staying accredited is absolutely critical to sustainability, since losing accreditation could mean loss of financial aid and public trust, which is often a death blow (we’ve seen for-profit colleges collapse after accreditation issues). But if you maintain good practices, that won’t happen. Think of accreditation as a continuous quality assurance partnership.

Adding Programs Strategically: Growth often involves expanding your academic offerings. Once your initial programs are stable, you can consider adding new programs or even schools/colleges within the university. The key word is strategically. Use data and feedback to guide expansion:

- Analyze what prospective students are asking for. If you notice a lot of inquiries for a program you don’t offer yet (say, you started with business degrees and people keep asking if you have accounting or finance specialization), that’s a clue.

- Look at job market trends and regional needs. If your area is becoming a tech hub, perhaps a computer science or data analytics program would attract interest. If you have a strong core in one discipline, consider logical extensions (e.g., a successful undergraduate psychology program could pave way for a master’s in counseling).

- Pilot and scale: You could introduce some programs as concentrations or minors first, then expand to full degrees if demand proves high. Or launch non-degree certificate programs (which are quicker to implement and can test the market) and later transition them into degree programs.

- Mind the resource requirements: New programs might need new faculty with different expertise, perhaps new labs or equipment. Make sure the finances align – a costly program like engineering should have sufficient student interest to justify the investment.

- Also ensure any new program fits your mission and brand. It’s fine to diversify, but keep a cohesive identity. A common pitfall is stretching into too many areas too quickly and diluting quality. It’s often better to be excellent in a few areas than mediocre in many.

Growing Impact and Reputation: Growth isn’t just about the number of students or programs; it’s about enhancing your university’s reputation and impact on society. Here are some ways to cultivate that:

- Faculty Research and Achievements: Encourage and support your faculty in research or community projects. When your professors publish papers, secure grants, or get media coverage for expert commentary, it raises the profile of your institution. Even if you’re teaching-focused, some research and innovation can set you apart (for example, your environmental science department might do local conservation projects – that’s impact).

- Student Achievements: Track and publicize what your students and alumni achieve. The first time one of your alumni starts a successful business, or wins an award, or even just lands a job at a prestigious company – celebrate it. Over the years, as the alumni base grows, their success becomes your success. Consider creating an alumni association early, even if small, to keep graduates engaged – they can mentor students, help with placements, and potentially donate later on.

- Community Engagement: A sustainable university is one that is valued by its community. Engage in service projects, open campus events to the public (like an annual lecture series, cultural events, or free workshops). This not only enriches students’ experience but also builds goodwill. For instance, if your city sees your university as a hub for community learning (maybe you offer summer courses for high schoolers, or host community college transfer fairs), they’ll advocate for you.

- Partnerships: Forge partnerships with industry and other educational institutions. You might collaborate with a local hospital to train nurses (if you expand to healthcare programs) or with a tech company for internships. Perhaps form articulation agreements with community colleges so their graduates can smoothly transfer into your programs – boosting your enrollment and providing opportunity for those students. Partnerships can also ease resource burdens (e.g., sharing a research facility, or co-hosting events).

- Adapting to Change: Over the long term, be prepared to adapt. The higher education landscape is dynamic – consider the rapid rise of online learning, or disruptions like the COVID-19 pandemic which forced remote learning. To stay sustainable, embrace innovation. Maybe years down the line you’ll adopt AI tutoring systems, or competency-based education models, or other new approaches. The institutions that last are those that evolve with the times while holding onto their core mission.

Financial Resilience: Earlier we discussed how education is recession-proof in terms of demand, but universities still need sound financial practices to be truly recession-resistant. Here are some long-term financial strategies:

- Build an Endowment: As a private university, an endowment (a invested fund where typically only the interest or a portion is used annually) is a safety net and source of steady income. When you’re new, you won’t have much of one, but as you cultivate donors (alumni, philanthropists, businesses), try to grow an endowment. Even a small endowment can support scholarships or special projects. A larger one can help you weather economic downturns by providing income when other sources (like enrollment or state grants) fluctuate.

- Diversify Revenue Streams: In addition to tuition, think of other revenues. Continuing education courses, professional training workshops, online programs that reach beyond your local region, summer programs for high school students, renting out campus facilities for conferences – many universities have multiple income streams. Some private universities even develop services or products (like a university press or a research park that generates patent income). Diversification can buffer against a hit to any single stream.

- Prudent Budgeting: As you grow, resist the temptation to overspend in good times. A common issue for many institutions is expanding administration or facilities too fast when enrollment booms, only to struggle if enrollment dips. Maintain a reserve fund. Do multi-year financial planning. Also, manage debt carefully – borrowing to build a new building might be necessary, but ensure you have realistic projections to pay it off. Essentially, apply sound business practices, but always aligned with your academic mission (for example, cost-cutting shouldn’t gut the quality of education; find efficiencies that don’t harm student experience).

- Plan for Recessions: Even though education is relatively stable, recessions can still impact things like fundraising (donors give less) or endowment investments (stock market dips). Have contingency plans. Perhaps create a scenario in your financial plan for a 10% enrollment drop and see how’d you adjust (freeze hires? increase marketing? offer more part-time study options to attract those who can’t afford full-time?). By thinking these through in advance, you won’t be caught off guard if tough times come.

Leadership and Governance: A sustainable university also needs strong leadership and good governance. As founder, you might have been doing a bit of everything at first. Over time, ensure you develop a solid leadership team – a provost or academic dean to handle academics, a finance director, etc. Also establish a Board of Trustees (if non-profit) or an advisory board (even if for-profit, having an external board can provide guidance and credibility). These boards should have people who care about the mission and bring expertise (in education, business, law, etc.). They can help with fundraising and connect you to broader networks. Plus, they provide continuity – universities often outlast their founders, and having governance structures ensures the institution carries on its mission beyond any one individual.