AI Ready University (1): Why AI Literacy Is the New Must-Have Graduate Skill

Understanding Accreditation for New Universities and Colleges: Regional vs. National

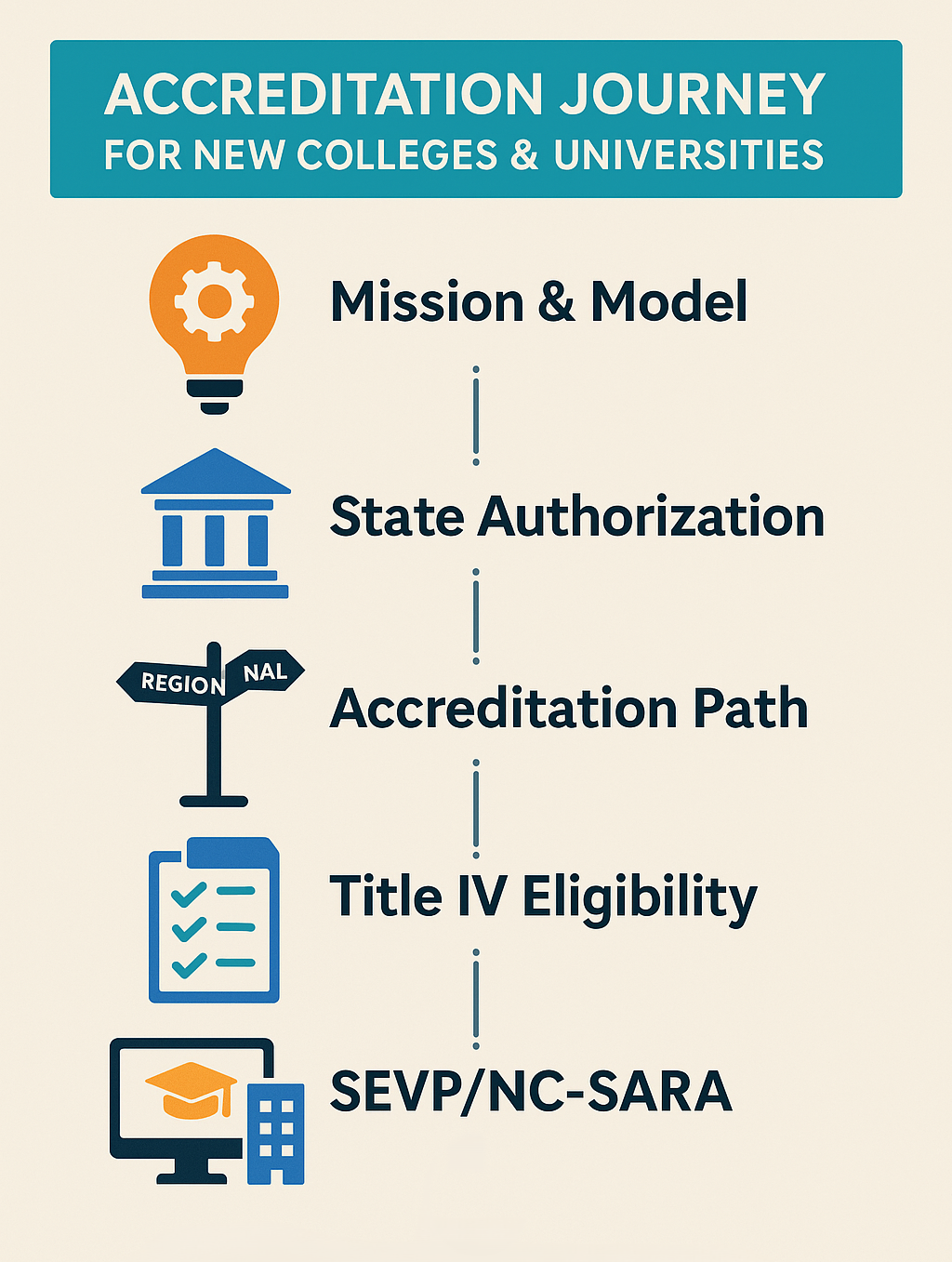

If you’re opening a college or university in the U.S., accreditation is your second hard gate after state authorization (the legal permission to operate and enroll students). Accreditation is an external peer‑review that evaluates whether you deliver on your mission, meet standards, and improve continuously. It also unlocks eligibility to apply for Title IV federal student aid after you meet other requirements.

This guide is a pragmatic, investor‑focused playbook on how to open a college or university with the right accreditation alignment. You’ll learn how “regional vs. national” works in 2025 (including changes since 2020 that removed geographic boundaries for historically regional accreditors), how to evaluate accreditors against your model (online‑first, allied health, hybrid), and how much does it cost to open a college or university when you factor in accreditation, staffing, systems, and state licensure. We define key terms in plain English, include selection matrices, timelines, a risk map, and a How‑To section you can implement immediately.

Where rules and recognition can change, we mark them “as of August 2025” and attribute to authoritative bodies in‑text: U.S. Department of Education (USDE), Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA), recognized institutional accreditors, NC‑SARA, and DHS/ICE for SEVP/SEVIS. Per your direction, no external links appear in this document.

Investor’s Blueprint: Mission, Model, Moat, and Proof

State authorization means your school has legal permission to operate in a given state. You cannot admit or teach students in that state until you are authorized or formally exempt. Institutional accreditation is a recognized, external quality assurance status at the institution level that evaluates governance, academics, student services, finances, and continuous improvement. Sources: U.S. Dept. of Education (August 2025); CHEA (August 2025).

1) Mission, model, moat

- Mission clarity: who you serve, what you teach, how learning is measured, and what student outcomes you will track.

- Model: on‑ground, online‑first, or hybrid. Online‑first lowers facilities costs but raises expectations for support, data integrity, accessibility, and instructor presence.

- Moat: licensure‑linked allied health, employer‑embedded projects, apprenticeships/clinicals, or distinctive pedagogy + analytics driving completion.

2) Academic scope and sequencing

Launch narrow (1–4 programs) and go deep. Sprawl undermines quality assurance and slows accreditation.

3) Governance that impresses evaluators

Seat an independent Board with conflict‑of‑interest controls. Empower a Chief Academic Officer (CAO) with real authority over curriculum, faculty qualifications, assessment, and substantive change. Publish and follow your policies.

4) Proofs of capacity

- Curriculum maps and outcomes‑assessment plan

- Faculty credentials mapped to course level (and documented tested experience where applicable)

- Student services (advising, tutoring, library/e‑resources, disability services)

- Financial discipline (audits, reserves, forecasting)

State Authorization (Licensure): Your Legal Gate

Every state sets its own rules for private postsecondary institutions. Expect applications, fees, surety instruments in some states, catalog/enrollment‑agreement review, facilities evidence (if on‑ground), and a site inspection. Founders who prepare well here get to accreditation faster.

Universal threads (as of August 2025)

- Corporate formation docs, bylaws, conflict‑of‑interest policy

- Programs and syllabi exemplars, credit‑hour policy, outcomes assessment plan

- Faculty roster with credentials at course level

- Student‑facing catalog + enrollment agreement (refunds, SAP, transfer, complaints)

- Facilities and safety records (on‑ground)

- Financial capacity and consumer‑protection controls

State selection moves cost and time

- California (BPPE): strict consumer protection; degree‑granting institutions face explicit accreditation timelines.

- Florida (CIE): structured application/inspection; LBMA option for accredited institutions.

- Texas (THECB/TWC): clear rules; surety expectations vary by scope.

- Arizona (Private Postsecondary Board): pragmatic checklists and timetables.

Institutional Accreditation: “Regional vs. National” in 2025 (What It Really Means)

Institutional accreditation affirms overall institutional quality. Programmatic accreditation validates specific programs and typically layers after institutional recognition. Sources: U.S. Dept. of Education and CHEA (August 2025).

The vocabulary—then and now

- Historically regional accreditors (e.g., SACSCOC, HLC, WSCUC, MSCHE, NECHE, NWCCU, ACCJC) traditionally served specific regions. In 2020, USDE removed geographic restrictions, but the term “regional” persists in practice. These bodies are often chosen by comprehensive, degree‑granting institutions with transfer pathways and graduate education. Source: U.S. Dept. of Education (August 2025).

- National accreditors (e.g., DEAC for distance education; ACCSC for career/technical) serve mission‑specific sectors. They are recognized by USDE and/or acknowledged by CHEA and can be the best fit for online‑first or career‑focused schools. Source: DEAC, ACCSC, CHEA (August 2025).

What accreditors evaluate (institutional)

- Mission and integrity

- Governance and administration

- Teaching and learning (outcomes, assessment, faculty qualifications)

- Student support and success (advising, library/e‑resources, accessibility)

- Planning, finances, and institutional effectiveness

- Transparency and consumer information

Typical stages

- Eligibility/Pre‑application (orientation + readiness)

- Candidacy/Pre‑accreditation (on‑site evaluation)

- Initial accreditation (after sustained compliance and outcomes evidence)

Regional vs. national—how to think like an investor

- Brand & transferability: Historically regional accreditors are widely recognized for transfer and graduate admissions; national accreditors are recognized but transfer acceptance varies by receiving institution (CHEA, August 2025).

- Modality fit: Online‑first schools often find DEAC a strong fit; hybrid/comprehensive institutions often align with historically regional accreditors.

- Operational history: Some national accreditors (e.g., ACCSC) require demonstrated operation before initial accreditation; some regional accreditors allow candidacy earlier if readiness is robust.

- Governance & evidence burden: All are rigorous. Historically regional accreditors emphasize longitudinal institutional effectiveness; national bodies emphasize mission‑fit performance within scope.

- Speed & cost: Varies by readiness, not just agency. Rushing multiplies risk.

- Downstream goals: Doctoral expansion, research partnerships, or extensive transfer ecosystems often point to historically regional; focused online‑first may point to DEAC; career/technical with labs may point to ACCSC.

Choosing Your Accreditor (Decision Matrix + Case Examples)

Use this matrix to shortlist accreditors by model and ambition. Timelines are ranges, as of August 2025.