AI Ready University (1): Why AI Literacy Is the New Must-Have Graduate Skill

What the “How to Open a College or University” Guides Won’t Tell You

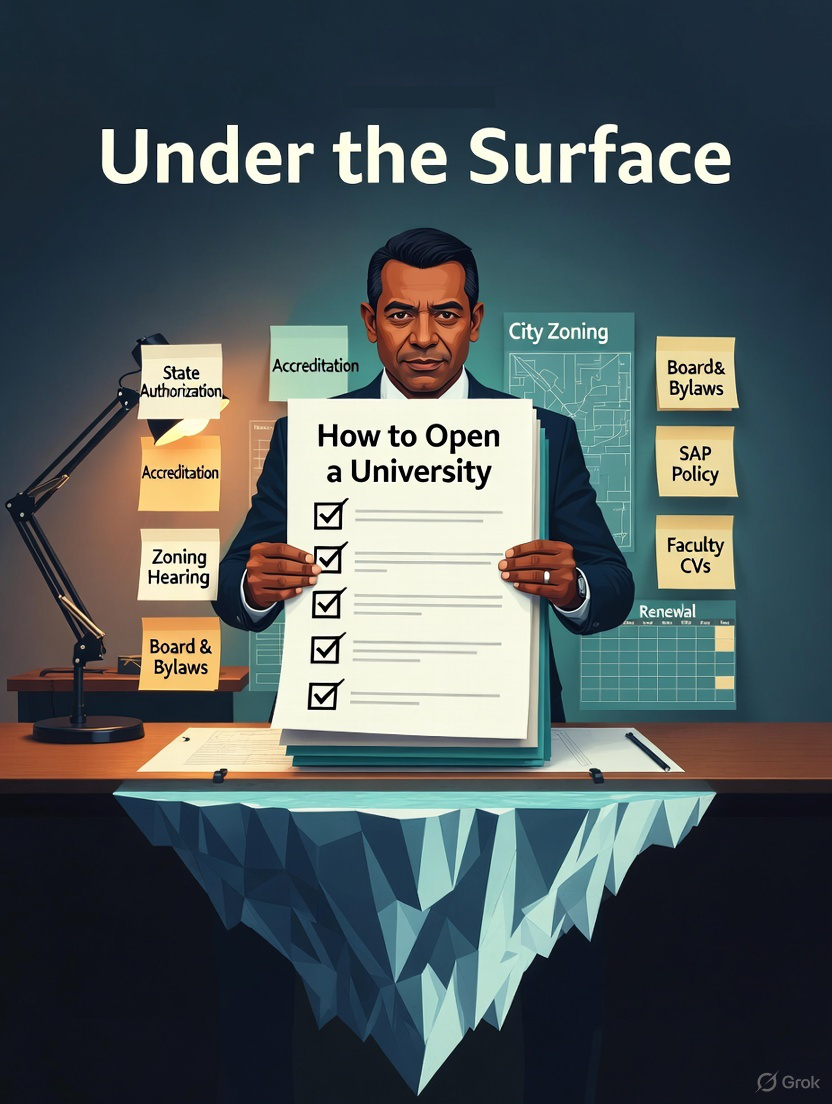

Opening a new college or university is an exciting venture – and a daunting one. If you’ve Googled how to open a college or university, you’ve probably seen the same basic advice repeated: form a legal entity, get a license, and figure out how much does it cost to open a college or university. Those starter guides cover the obvious: paperwork, budgets, and accreditation checklists. But any seasoned education founder or accreditation consultant will tell you there’s more to the story. Beyond the standard “to-do” list lurk less obvious hurdles that generic guides gloss over – from local zoning laws and community pushback, to assembling a credible faculty and board long before you welcome your first student.

If you’re an investor or entrepreneur (domestic or international) aiming to launch a higher education institution in the United States, this candid guide will prepare you for the real road ahead. We’ll bridge the gap between the rosy checklists and on-the-ground reality. Yes, we’ll cover the fundamentals of opening a college or university – but more importantly, we’ll dive into the advanced insights that typical “how-to” posts ignore. You’ll learn how to navigate hidden accreditation snags, avoid community and regulatory pitfalls, and set your venture on a path that’s both compliant and credible from day one. Let’s get started on what those other guides won’t tell you.

Understanding the Basics (Licensing, Accreditation, and Models)

Before we get to the uncommon challenges, let’s ensure we’re on the same page with some basic definitions and models. Launching a degree-granting institution involves two key approvals in the U.S., plus choices about your school’s structure and scope:

- State Authorization vs. Accreditation: These are not the same thing. State authorization (or licensure) is your legal license to operate as a college in a given state. Without it, you generally cannot even call yourself a “university” or enroll students for degrees – it’s actually illegal to do so without state approval. Each state has its own process and standards (usually via a higher education department or board), designed for consumer protection and basic quality control. Think of it as the state giving you permission to open your doors. Accreditation, on the other hand, is a voluntary quality stamp granted by independent agencies (not the government) that signals your institution meets certain academic standards. While technically optional, accreditation becomes essential in the long run – it’s required for students to access federal financial aid and it greatly boosts your credibility for credit transfers and employer recognition. In short, state authorization lets you operate; accreditation proves your quality. And the order matters: you must get state licensed first, launch programs, and typically operate for at least a year (with students and actual outcomes) before an accrediting body will even consider your application. Most states likewise expect you to achieve accreditation within a certain timeframe after launching.

- Legal Entity and Governance: To start any school, you’ll need to establish a legal entity (e.g. a nonprofit corporation or an LLC/for-profit corporation) and a governance structure. For-profit vs. non-profit is a pivotal choice. A non-profit college can seek 501(c)(3) tax-exempt status (meaning donations are tax-deductible and you may be eligible for certain grants), but it comes with stricter governance (an independent board of trustees) and no owners/shareholders – any “profit” is reinvested in the institution. A for-profit college can distribute profits to owners or investors and often has more management flexibility, but may face more skepticism from regulators and accreditors on issues of academic independence and consumer protection. Both models can succeed, but be mindful of the trade-offs: for-profits might attract equity investment, whereas non-profits might attract philanthropic support. In either case, establishing a qualified board and leadership team early is critical. Don’t wait until after you’re licensed to figure out who’s overseeing academics and compliance – show regulators you have experienced people at the helm from the start. (In fact, many states require you to list owners, directors, and key administrators in the application. If it’s a non-profit, expect to provide bylaws and board member details; if it’s a for-profit, you’ll disclose ownership and any parent companies.)

- Licensure, Exemptions, and “Religious” Institutions: The scope of what you plan to offer affects how you’ll be regulated. If you’re launching a standard college offering secular degrees (Associate’s, Bachelor’s, Master’s, etc.), you will fall under your state’s higher education licensing requirements. Some specialized models exist: for example, a religious-exempt college or seminary. A “religious-exempt” institution is one that offers only religious/theological programs (often under a church’s ownership) and no secular degrees. In states that allow this exemption, such schools can bypass the full licensing process if they strictly limit themselves to faith-based education. Typically, they must label all degrees as religious (e.g. “Bachelor of Biblical Studies” rather than B.A.), file a simple notice or affidavit with the state, and avoid secular subjects or federal student aid. Not all states offer this exemption (New York, for instance, has no religious carve-out – everyone must go through the Board of Regents), whereas states like Florida and Texas do allow it with certain paperwork. The takeaway: unless you’re planning a seminary, expect to go through the full state authorization process – but know that these niche exemptions exist if your model is faith-based.

- Domestic vs. International Founders: If you’re a U.S.-based entrepreneur, forming a business entity and navigating the state process might feel familiar. If you’re an international investor or founder aiming to open a U.S. college, you should know that foreigners can indeed establish U.S. institutions. You’ll need to register a company in the state you choose (usually through a local attorney or service) and appoint a registered agent with a local address to receive official communications. There’s no citizenship requirement for owning a school, but you must follow all U.S. laws (e.g. if you plan to reside in the U.S. to run the school, you’ll need appropriate visas – another topic entirely). The key is picking a state whose regulations you understand and maybe hiring local expertise to manage compliance. We’ll talk more about choosing a friendly jurisdiction next.

Now that we’ve defined the essentials – state license vs. accreditation, entity types, and special models – let’s weigh the big-picture pros and cons of jumping into this industry.

Benefits and Trade-offs of Starting a University (and How to Mitigate Risks)

Launching a new college or university can be incredibly rewarding. It’s an opportunity to fill an educational gap, shape the learning experience from scratch, and potentially create a lasting institution. But it’s also rife with risks and trade-offs. Below is a balanced look at the potential benefits alongside the trade-offs and how savvy founders mitigate them:

- Benefit: A Clear Educational Mission and Market Need – Perhaps you see a demand that existing colleges aren’t meeting (e.g. an online workforce-focused college in a niche field, or a new university in a growing community that lacks one). Being mission-driven can attract students, talent, and even donors. Trade-off: Mission alone doesn’t guarantee survival. If the market need is smaller than expected or competition moves in, you could struggle with enrollment. Mitigation: Do your homework with a feasibility study and market analysis. Identify a niche where you can excel. Start with a focused set of programs that play to your strengths. Also, articulate how you’ll adapt if initial enrollment is slow – for example, will you have continuing education or non-degree courses as alternative revenue? Plan for multiple scenarios.

- Benefit: Control and Innovation – As a founder, you get to design programs, curriculum, and student services the way you envision, unencumbered by legacy bureaucracy. You can innovate with new teaching methods, tech platforms, or partnerships. Trade-off: Innovation in education still operates within strict regulatory guardrails. You might want to offer an unorthodox curriculum or a radical pricing model, but accreditors and state regulators have standards you must meet (for example, credit hour definitions, faculty qualification requirements, etc.). Mitigation: Build credibility with a mix of innovation and adherence to quality norms. For any novel idea, cross-check it against accreditation standards or get a consultant’s input early. Often, you can pilot new approaches (say, a project-based learning module) within a traditional framework to satisfy regulators. Document everything to show how student learning is achieved equivalently if you deviate from the norm.

- Benefit: Economic and Social Impact – A new college can create jobs and become an anchor institution in the community. Founders driven by a social mission (like increasing access for underrepresented students) can truly make a difference. Trade-off: You may face community or political resistance. Surprisingly, not everyone will cheer for a new college. Local residents might worry about traffic or student housing issues; existing colleges might view you as unwanted competition. For instance, in New York, when a new degree institution is proposed, the state actually canvasses existing colleges to raise any concerns about the impact on them. It’s a formal chance for competitors to object! Similarly, local zoning boards might push back on your campus plans – it’s common that universities and their host communities “don’t always see eye to eye” on expansion or new development. Mitigation: Engage early and often with stakeholders. If you’re setting up a physical campus, attend local meetings, address neighborhood concerns (like traffic mitigation or security plans), and highlight the benefits (jobs, cultural offerings, etc.) your school will bring. Consider forming a community advisory board. In states with formal review input (like NY’s canvassing), prepare solid justifications for how your programs serve unmet needs (so other colleges have less ground to object). Transparent communication can turn wary neighbors into partners. Remember, a university can be an anchor that lifts the local economy – emphasize that narrative.

- Benefit: Long-Term Financial Opportunity – Education can be both a noble cause and a sustainable business. With the right model, tuition and funding streams (grants, contracts, etc.) can eventually make the institution self-supporting or profitable. There’s also prestige and legacy in founding an institution that might last for generations. Trade-off: The upfront costs and financial risks are significant. Campuses, faculty salaries, technology – it adds up quickly, and returns (tuition revenue) take time to materialize. Unlike a typical startup, you can’t scale overnight or pivot easily if the financial model falters; you’re dealing with students’ lives and regulatory commitments. Mitigation: De-risk your financial plan. Seasoned education investors insist on conservative budgeting and buffers. Set aside extra contingency funds and don’t bank on best-case enrollment from day one. It’s wise to secure diverse funding: a mix of investor capital, perhaps initial donations or grants, and realistic tuition pricing. Also consider starting small (even as an online college or a single program) to manage costs, then scaling once you have momentum. We’ll provide a detailed cost breakdown later in this guide – use it to double-check that you haven’t underestimated any major expenses or overestimated revenues.

- Benefit: Path to Accreditation and Growth – If you succeed in building a quality institution, accreditation and recognition will open doors. Accredited colleges can participate in federal financial aid programs and are generally more trusted by employers and other universities. Being the founder of an accredited university can also raise your professional profile significantly. Trade-off: Accreditation is a long, challenging journey, not a one-time box to check. Initial accreditation typically takes several years of preparation and review. During this time, you must maintain top-notch academic standards often without the benefit of Title IV federal aid for your students (meaning you need to attract students who can pay out-of-pocket or via private loans initially). There’s a “chicken-and-egg” challenge: you need to prove quality to get accredited, but lacking accreditation can make recruiting students harder. Mitigation: Treat quality assurance as integral from day zero. Don’t wait until year 3 to think about accreditation. Implement policies for curriculum review, student assessment, faculty hiring, and governance that mirror accreditor expectations (we’ll detail some in Quality & Credibility below). Many founders do a mock accreditation audit early or hire an accreditation consultant for a readiness check. By building a culture of continuous improvement and evidence (tracking student outcomes, gathering feedback, etc.), you’ll not only smooth the path to accreditation but also run a better school in the meantime. It’s about creating a virtuous cycle: quality leads to accreditation, which then allows you to grow and reinvest in quality.

In summary, opening a college or university offers huge upsides – personal fulfillment, societal impact, and financial reward – but it comes with equally large responsibilities and risks. By anticipating the trade-offs and planning mitigations as above, you set yourself up to reap the benefits while keeping pitfalls at bay. Next, let’s get into the concrete steps of laying your institutional foundation.

Foundational Setup: From Entity Formation to Bank Accounts and Beyond

With your vision and game plan in mind, it’s time to get the foundational pieces in place. Think of this as setting up the “plumbing” and guardrails of your institution – the less glamorous paperwork and compliance steps that nonetheless are absolutely non-negotiable. Neglecting these early can derail your launch before it even begins.

1. Form Your Legal Entity and Governance Structure: Every college begins as a legal entity. Choose a state and incorporate either as a nonprofit or a for-profit business, depending on your model. Most new degree-granting institutions in the U.S. incorporate as nonprofits (to signal a public service mission and qualify for tax exemption), but some are for-profit (especially many online career colleges). File Articles of Incorporation with your chosen state and fulfill any other incorporation steps (like drafting bylaws for a nonprofit or an operating agreement for an LLC). Pro Tip: If you plan to seek 501(c)(3) status from the IRS (tax-exempt nonprofit), your purpose and governance documents must align with charitable educational purposes and you’ll need a board of directors/trustees (at least 3 unrelated members is a common requirement). Set up your initial board or management team. Even if you as the founder hold a primary leadership role (CEO/President), regulators will want to see that you have qualified academic oversight and a system of checks and balances. For a nonprofit, that means an independent board governing the institution’s mission and finances. For a for-profit, it might mean an academic advisory board or clearly defined roles like a Chief Academic Officer who has appropriate credentials. Start recruiting credible names for these roles early – think retired university administrators, experienced faculty, or industry leaders who believe in your mission. A strong governance and leadership roster will instantly boost your credibility with regulators and accreditors.

2. Banking and Finance Setup: Once your entity exists, open a dedicated business bank account for the college. This is where you’ll deposit initial capital and later, tuition revenues. Keeping finances separate from your personal accounts is critical for transparency. Many states actually require proof of financial stability as part of licensing – for example, showing a minimum cash balance or liquidity. (In one lean startup scenario, founders needed to show at least $100,000 in a bank account as proof of solvency for state approval) You should also set up proper accounting (consider hiring an accountant who has worked with educational institutions). If you plan to handle federal funds down the road (Title IV financial aid), you’ll be subject to annual audits, so it’s wise to institute sound financial controls from the beginning. Additionally, consider obtaining basic insurance – general liability (especially if you have a campus), directors & officers insurance for your board, and perhaps educational liability insurance.

3. Tax-Exempt Status and Charitable Considerations (if applicable): If operating as a nonprofit, you’ll likely apply to the IRS for 501(c)(3) status. This process can take several months, but it’s important if you want to solicit donations or grants. Many foundations and donors will only give to 501(c)(3) entities. To apply, you’ll need a detailed description of your activities, budgets, and conflict-of-interest policies for your board. If you’re international and opting for a for-profit model, be aware of U.S. taxes on any income; consult a tax professional to structure things efficiently (for example, foreign owners might set up a U.S. subsidiary to limit tax exposure). Also, even if you’re a for-profit, consider setting up a scholarship fund or foundation alongside your college – this can provide financial aid to students and demonstrate your commitment to access (it’s a good look for accreditors, who care about student support, and communities).

4. Required Policies and Disclosures: This is a big one that many “how to open” lists fail to emphasize. Before you ever enroll a student, you must have a thorough catalog and policy handbook drafted. States will demand it as part of your license application, and accreditors will scrutinize it later. Expect to prepare and disclose policies on: admissions criteria, transfer credit, tuition and fees, refund policies (how you handle withdrawals), academic integrity, grading systems, student code of conduct, faculty qualifications, complaint/grievance procedures, Satisfactory Academic Progress (SAP) standards (e.g. how you measure if students are progressing adequately – often needed for financial aid purposes), privacy and record-keeping, and more. You’ll need an academic catalog that describes each program in detail (course descriptions, credit hours, learning outcomes) and the credentials of faculty teaching those courses. Some states require that you submit this catalog to them and even to prospective students upfront. Don’t cut corners here. These documents are essentially the contract between your university and the student; they also serve as evidence to regulators that you know what you’re doing. As an example, one state’s licensing checklist might include: list of faculty with degrees, course catalog, grievance policy, sample student transcript, description of facilities, financial plan, organizational chart, etc. Indeed, some states insist that you have signed employment agreements or commitment letters from faculty as part of the application – proving you’ve already lined up qualified educators before they’ll approve you to operate. Ensure all your materials are clear, professional, and compliant with any state-specific rules (like required consumer disclosures). If writing policies isn’t your forte, this is a good time to bring in that accreditation or compliance consultant to help craft policies that meet regulatory standards. It’s easier to do it right at the start than to rewrite everything later after a regulator’s critique.

5. Setting Up Administrative Systems: Even before you have students, consider what systems you will use to manage records. You’ll need at minimum a secure student information system (SIS) for tracking enrollments, grades, and transcripts, and likely a learning management system (LMS) if you’re delivering content online (more on tech in the Cost section). Establish protocols for student records retention – many states require you keep academic records for decades (some say transcripts must be kept 50+ years or permanently). If you close or cease operation, you’re often required to transfer records to the state or a repository. Having a plan for records management from day one is part of being a trustworthy institution.

6. Compliance and Reporting Mechanisms: Finally, set up calendars and responsibility lists for ongoing compliance. This includes things like: annual corporate filings to keep your entity in good standing, renewal deadlines for your state authorization (which could be annual if you’re unaccredited – e.g. many states give an initial one-year license that you must renew until you become accredited), and any required reporting (some states ask for yearly enrollment and financial reports). Put these dates on autopilot reminders; falling out of compliance on a technicality (like missing a renewal deadline) can incur fines or even jeopardize your operating license. Treat compliance as a continual process, not a one-time project.

With your institution legally and structurally established – entity, bank account, policies, and systems – you have built a solid foundation. Next, we’ll discuss how the specific location or jurisdiction you choose can profoundly shape your path, and what to consider when picking where (and how) to operate.

Jurisdiction and Market Considerations: Choosing Where and How You’ll Operate

Education in the U.S. is highly decentralized, meaning the rules to open a college can vary dramatically by state. Your choice of jurisdiction (which state, or states, you will operate in) will influence everything from how hard it is to get licensed, to how much it costs, to what programs you can offer. Let’s break down some key considerations and compare a few examples. (Even if you already have a home state in mind, this section will alert you to what specifics to verify for that market.)

What’s Allowed and Who Regulates? Every state has an agency or authority that oversees higher education licensing. However, some states are more permissive than others. For instance, some states readily allow for-profit degree institutions and have a straightforward process; others, like New York, treat all new colleges to a rigorous review including public hearings or canvassing of existing institutions. A few states (especially those with smaller populations) might have less detailed regulations, but don’t assume any state is a free-for-all – using the term “college” or “university” is legally protected in most places, so you must engage with the state oversight one way or another. Also, consider the types of degrees you plan to offer. In certain jurisdictions, offering higher-level degrees (Master’s, PhD) might trigger additional scrutiny or requirements (e.g. proving you have faculty with doctorates, or separate approval for each degree level).

Physical Presence vs. Online: Are you opening a physical campus, or an online university serving students nationally? This distinction matters. Generally, you must be authorized in the state where you have a physical presence (like a campus or office). If you’re online-only, you’ll license in the state where your main offices are located. Teaching students in other states via distance learning introduces the concept of SARA (State Authorization Reciprocity Agreement) – an agreement covering 49 states that simplifies offering online programs across state lines. If your home state is part of SARA (most are, except California), once you’re authorized and you join SARA, you can enroll online students from other member states without needing separate licenses in each. This is a huge benefit for online institutions – it means you don’t have to chase approvals in, say, Texas, New York, or Illinois individually (with the notable caveat that California, not in SARA, requires its own authorization if you target CA students). If you plan a national online strategy, choosing a SARA-member state for your base is wise. If you plan to open branch campuses in multiple states, be prepared to go through licensing in each (though starting with one campus and expanding later is usually more feasible).

Local Environment and Demand: The state or city you choose also determines your competitive and community environment. Setting up a new college in a state with many existing institutions (and perhaps declining student populations) might invite more scrutiny or opposition. On the other hand, states that actively promote themselves as education-friendly (perhaps to attract investment) might roll out the red carpet. For example, some states in the past decade have streamlined their approval processes to encourage innovative online universities or to become hubs for international education. Ask: is the region underserved in the niche you plan to fill, or saturated? Also research if any state-specific incentives exist – occasionally, states offer grants or support for institutions that address workforce needs in high-demand fields.

To illustrate how requirements can differ, here’s a snapshot comparison of a few jurisdictions and their key expectations:

(The table is for example only – always verify current regulations in your target state, as rules can change.)

A Note on Changing Rules: Keep in mind that state regulations evolve. Budget cuts, political shifts, or scandals can prompt states to tighten oversight or, conversely, to deregulate. For example, a state that had no requirements for online schools might introduce a registration mandate next year. Always check the latest laws and, if possible, speak to the state regulatory agency early in your planning. Many have guidance documents or even will do informational calls to help new institutions understand the process. Also, some states have different processes for non-degree postsecondary programs vs. degree-granting – our focus here is degree-granting, but if you decided to start by offering certificate programs (non-degree) to build a track record, you might fall under a different (often easier) approval path initially.

Local Zoning and Facilities: Another aspect of “jurisdiction” is at the city/county level – if you’re establishing a physical campus or learning site. Local governments control zoning – whether a property can be used as a school. Educational use is often allowed in institutional or certain commercial zones, but you may need a special permit, especially if you’re converting a building. Be prepared to submit campus site plans or comply with local building codes (e.g. adding fire safety systems, ADA accommodations). Don’t overlook things like parking requirements or occupancy limits. Engaging an architect or facilities planner who has done school or campus projects can save you headaches. Remember the earlier point: sometimes residents object to new campus developments. Following local procedures meticulously and demonstrating that you’ll be a responsible neighbor (traffic management, security, good landscaping, etc.) will ease the path.

In summary, choose your “home base” wisely. A state that aligns with your vision (regulation-wise and market-wise) can make a huge difference. A favorable jurisdiction can mean lower startup costs and quicker launch; a challenging one can mean delays and expenses but might lend more prestige or access (e.g. New York authorization carries weight). There’s no one-size-fits-all answer – the key is to do a comparative analysis as we’ve outlined, and ensure you’re fully aware of what’s expected in your chosen locale.

Next, let’s outline the actual step-by-step roadmap from Day 1 of your project to the day you open your doors (virtually or physically) – including a rough timeline of key milestones.

Step-by-Step Roadmap to Opening a College or University (Timeline with Milestones)

Starting a university is a process that unfolds over months and years, not weeks. However, it helps to break it into manageable phases. Below is a generalized timeline and roadmap, assuming you’re building from scratch. Your actual timeline may vary (some steps overlap and some might take longer in certain states), but this gives an order-of-operations and realistic timeframes for a U.S. context.

Weeks 0–4: Ideation, Research, and Entity Setup

Milestone: Refine concept and form the organization. In the first few weeks, you’ll move from idea to action plan. Key tasks include: conducting initial market research (e.g. confirm the demand for your programs, survey local or online potential students, scan competitor offerings), and writing a high-level business plan. This business plan should outline your mission, target student population, academic focus (fields of study), revenue model (tuition projections, etc.), and basic expense estimates. You don’t need a 100-page tome – but you do need a coherent plan because you’ll likely have to submit parts of it to regulators or investors. Simultaneously, start assembling your founding team. Identify a project leader (often this is you, the founder/CEO) and other co-founders or advisors – especially someone who understands academics (perhaps a former dean or professor who can advise on curriculum). Begin networking for potential board members or key staff (you might not formally hire them yet, but line up commitments).

By the end of Week 4, aim to formally register your legal entity (LLC, corporation, etc.) with the state. This gives you an official name and standing (and you’ll need that to do things like open a bank account or sign contracts). Pro tip: Before registering, do a quick check if the name you want (e.g. “Example University”) is legally allowed. Some states require approval to use “University” or “College” in your business name – often the education agency must sign off. In some cases, you may incorporate with a placeholder name and later adopt the “University” name upon state education approval. Also, in these early weeks, set up a basic website domain and email for professional communications (even if the full site comes later). It helps to correspond with regulators using an official university domain email.

Months 1–3: Licensing Prep and Initial Infrastructure

Milestone: Prepare the state application and foundational documents. This phase is paperwork-heavy. Once you know where you are applying (state chosen) and your concept is solid, download or request the state’s application packet for new institutions. It will read like a checklist of everything to submit – typically: your business incorporation proof, detailed business plan (with 3-5 year financial projections), program outlines and course descriptions, draft catalog/student handbook, faculty list or hiring plan, description of facilities, organizational charts, and so on. It can be overwhelming, but break it down item by item. If you haven’t already, this is when you write all your policies and compile them into a draft catalog as discussed earlier. Also, secure tentative faculty commitments. For each program or major subject area, you’ll need at least one qualified instructor identified (states want to see you have the academic personnel lined up). This might mean advertising for faculty or tapping your network. You may not hire them full-time yet, but get letters of intent or resumes you can include in the application. It’s common to include CVs of your key faculty and administrators in the submission.

Concurrently, address the physical or digital infrastructure: If you plan a physical campus or even a small office, start scouting locations and checking zoning feasibility. If leasing a space, you might sign a contingent lease (contingent on getting state approval) or at least get a letter of intent from a landlord. If you’re going online, decide on your technology platforms – you don’t necessarily need to have the LMS fully set up by month 3, but you should have a plan (e.g. will you use a cloud-based LMS, which one, what IT support you need). Get quotes if you need to include tech costs in your budget. Set up a basic website during this phase as well – even a simple landing page that says “Coming Soon: [Your University Name], opening in [Year]” with some info – because regulators often check if you have a web presence. However, be careful: do not start advertising or enrolling students yet, and ensure the site clearly states that programs are “pending approval” if you mention offerings. Many states strictly prohibit advertising a college or taking student money until you are licensed, so your messaging must be preliminary.

By the end of Month 3, you should ideally have a near-complete application dossier ready for state review. It might not be submitted yet (some founders take 4-6 months to polish it), but having all pieces drafted is a major milestone. It means the curriculum is designed, the budget is worked out, and the key staff are identified.

Months 4–6: Submit Application, Feedback, and Pre-Launch Work

Milestone: Obtain state authorization (provisional) and start operational setup. Early in this window, you will submit your state license application. This could be an online portal submission (many states have moved to online systems) or a physical mailing. Pay the required fee (ranges from a few hundred to several thousand dollars as noted – e.g. $850 in some states, up to $10,000+ in others). Once submitted, there’s typically a waiting period while officials review your documents. They will check for completeness and compliance. Be prepared for questions or requests for additional information – this is normal. Maybe they want clarification on a curriculum detail, or they ask for a higher surety bond amount after reviewing your projected tuition revenues. Respond promptly to any such feedback. If the state schedules a meeting or site visit, use this time to prepare. For a site visit, organize all your files, ensure any physical space is presentable, and even practice answering questions. Some states do a preliminary staff review and then a board or commission vote. If you have the opportunity to attend a hearing or meeting when your application is considered, do it – and bring your academic leader or another credible representative to help address any academic questions.

During the downtime while waiting, focus on operational preparations. Finalize your branding (logo, seal, etc.), and start developing your marketing strategy (but again, don’t launch recruitment until authorized). You can draft marketing materials, set up social media channels ready to activate, and build out your website fully (keeping language careful about “pending approval” until you have the green light). Also, begin establishing partnerships: for instance, if you want to have internships for students, reach out to local companies or institutions to line those up. Or if you need an agreement for library resources or online databases, negotiate those subscriptions now.

By around Month 6, with luck, you receive state approval – often initially a provisional license or “authorization to operate” for a limited term (commonly one year, especially if you’re not accredited yet). Congratulations – you are now legally a university! This is a huge milestone. You’ll get a certificate or letter from the state saying you’re authorized to offer XYZ degrees. In some states, you might also need to seek degree-granting authority for each degree level (some call this degree authorization separate from institutional license). Usually it’s part of the same process, but double-check that the approval indeed covers all the programs/degrees you intend to launch.

Months 6–12: Launching Academic Operations and First Students

Milestone: Enroll first students and commence instruction (pilot phase). After getting licensed, your focus shifts to actually running the school. Key tasks now: finalize faculty hiring (convert those tentative agreements into signed contracts and get instructors on payroll as needed), open admissions – publish application forms on your website, start advertising, and begin recruiting students for your first cohort. It’s common to allow a 3-6 month lead time to recruit before classes start. Ensure you have a student application management process in place (even if it’s just an email and spreadsheet for the first few applicants, or a basic admissions software). Also, set up your student services basics: how will you handle student inquiries, advising, tech support for online students, etc.? Even if you’re small, assign someone (or yourself) to be the go-to contact for enrolled students.

Meanwhile, tie up any loose compliance ends. For example, if the state license came with conditions (“you must submit a progress report in 6 months” or “limited to X students until first renewal”), note those. If you plan to seek accreditation eventually, now – before students arrive – is a good time to map out an accreditation game plan. Research accrediting agencies to decide which fits your mission (regional vs national, as discussed in the Primer). Many accrediting bodies have an eligibility application or candidacy stage; read those requirements now. Typically, you cannot apply until you’ve operated for a bit, but you often can signal your intent or start aligning your processes. You might consider hiring an accreditation consultant around this time to conduct a “gap analysis” – basically, review your current setup vs. accreditor standards to see what to improve. This doesn’t mean you’re going for accreditation immediately, but it sets you on the right track (and some consultants have insights that also help in running the school better from day one).

If you have a physical campus, by month 6–12 you should be readying the facilities for students – furniture, signage, IT infrastructure, library setup, etc. If online, you should be testing your LMS with faculty, loading course content, and maybe running a small beta test or demo course to iron out technical kinks.

Finally, when you have enough admitted students, start classes! This could be around month 9 or 12 depending on your recruitment cycle. Some new institutions target a soft launch (maybe a short semester or a pilot program) to get feedback and testimonials, then ramp up enrollment in the next term.

Month 12 and Beyond: Evaluation, Improvement, and Growth

Milestone: Complete first academic cycle and prepare for accreditation. After a year, you’ll have actual outcomes – students who completed courses, maybe some who graduated if it was a short program, or at least data on retention and satisfaction. Review these critically. Conduct student evaluations of courses, hold faculty meetings to discuss what worked and what didn’t. Regulators and accreditors love to see that you have an “assessment loop” – that you gather feedback and use it to improve. So document any changes or improvements you implement in curriculum or policy as a result of the first year’s experience.

By the end of year 1 or start of year 2, many new colleges initiate the formal accreditation application. Depending on the accreditor, you might submit an Eligibility Application (basically proving you meet basic criteria), then achieve “Candidate” status after review and a site visit, and finally full accreditation after perhaps 2 years of candidacy. It’s not uncommon for the full accreditation to take 3-5 years from launch, but making progress is crucial. Some states mandate that within, say, 5 years of operation you must have achieved accreditation or be well on your way – otherwise they might not renew your license indefinitely. So treat accreditation progress as a key part of your timeline beyond the first year.

Parallel to accreditation, you will be focusing on scaling up: adding new programs or concentrations (based on demand), hiring more faculty as enrollment grows, and possibly expanding facilities or student support services. Each new program might require state notification or approval, so factor in mini-timelines for those as well (e.g. adding a new degree might take a few months for the state to OK it, even if you’re already licensed).

Throughout this journey, maintain a detailed project plan with tasks and deadlines. Opening a university involves interplay of academics, compliance, facilities, and marketing – it’s a project manager’s challenge. Many founders find it useful to create a Gantt chart or use project management software to track the myriad steps and who’s responsible for each.

To recap this section: patience and persistence are key. From the first planning day to the first class day can easily be 12-18 months or more, depending on the regulatory climate. Don’t rush through steps like writing your curriculum or policies – doing them properly saves time later when under review. Celebrate small milestones (submitted the application, got the license, enrolled the first student) – each is a step toward the larger vision. And always keep an eye on the next milestone: as soon as you get your license, think about accreditation; as soon as you start classes, think about first graduation and outcomes; as soon as you get accredited, think about sustainable growth.

Next, one of the most common questions founders ask: what will this all cost? We’ve hinted at fees and budgets, but let’s do a dedicated breakdown of the costs to open a college or university.

Cost Breakdown: How Much Does It Cost to Open a College or University?

Money is often the make-or-break factor in turning your educational dream into reality. So, how much does it cost to open a college or university? The honest answer: it varies widely based on your scale and model. You can start a modest online college with a lean budget (tens of thousands of dollars) or invest tens of millions into a residential campus. Let’s break down the typical cost categories and give some ranges to calibrate your expectations. Remember, you can control some cost “levers” – doing things in-house vs. outsourcing, starting small vs. big – and we’ll note those as well.

1. Business Setup and Licensing Fees: This is the first bucket of expenses you’ll encounter. Forming a legal entity might cost a few hundred dollars in state filing fees. The state licensing application fee can range: for example, Florida’s application fee is around $800-900, while New York’s is $7,000 (plus $2,500 for each additional degree program). Some states charge modest fees for background checks, name registration, or a required surety bond. A surety bond is a form of insurance some states require to protect students – you don’t pay the full bond amount upfront, but you pay an annual premium (perhaps $250–$1,000 a year depending on bond size and your credit). Budget a few thousand dollars in total for the initial licensing-related fees and corporate setup.

2. Facilities (Campus or Office): Facilities will likely be your biggest fixed cost if you are doing any on-site instruction. The price swings depend on location and size. Consider these benchmarks: In high-cost states like New York or California, renting even a modest facility can run $10,000–$20,000 per month. That would get you perhaps a few classrooms and offices in an urban area. In more affordable states like Florida, Arizona, or Utah, similar space might be $5,000–$10,000 per month. If you only need a small administrative office (say, for an online university with no on-campus students), you could find coworking or shared office space for as little as $500–$1,000 a month. Keep in mind, even online institutions need a physical address – regulators want a real office, not just a P.O. box. When budgeting facilities, also factor in utilities, insurance, and maintenance. If your programs require specialized spaces (labs for science, workshops for vocational programs), the costs shoot up – lab equipment and safety installations can cost tens of thousands more. Some founders mitigate facility costs by renting from existing schools during off-hours or partnering with a local institution for space – a creative solution if you only need occasional in-person sessions.

3. Faculty and Staff Salaries: Human capital is both critical and expensive. A college is nothing without qualified educators and administrators. Typical full-time faculty salaries range from about $60,000 at the low end to $150,000+ for senior or specialized fields. If you’re a niche graduate school or in a pricey metro, the upper end could be even higher, but many new teaching-focused institutions start faculty in the $60k–$80k range for core instructors. Adjunct faculty (part-time teachers paid per course) might cost $2,000–$5,000 per course taught in many fields– though in high-demand fields or big cities, it can go up to $10,000 for a semester course. You can control costs initially by relying more on adjuncts or part-time faculty, but accreditors will expect you to eventually have a stable core of full-time faculty for academic continuity.

On the administrative staff side, consider roles like a registrar, an admissions officer, a financial officer, IT support, and student services personnel. In the very beginning, people wear multiple hats – e.g. the founder might also be acting President and CFO; one admin might handle both registrar and admissions tasks for the first 20 students. But as you grow, these will split into distinct jobs. Salaries or hourly rates vary widely: for instance, an experienced registrar or director of admissions might command $60k–$80k, whereas a part-time bookkeeper or IT support might be at an hourly $40–$100/hour rate. The range for skilled administrative roles can be $40 up to $250 per hour on a contract basis. To save costs early, you might hire some on a consulting or part-time basis – say, a part-time Chief Academic Officer consultant to help set up academic policies, or a contract web developer instead of an in-house IT team. Assume at minimum you’ll have a few full-time equivalent (FTE) staff on payroll by the time you launch – budget perhaps $150,000–$300,000 total for first-year payroll (that could cover a handful of roles and some adjunct teaching costs). This can be lower if you are extremely small-scale and founder-driven (founder not taking salary initially, etc.), or higher if you front-load hires for quality.

4. Curriculum and Content Development: Don’t forget the cost to actually develop your courses and materials. If your founding team includes subject matter experts, you might create a curriculum in-house. The cost here is mainly time (unpaid labor or sweat equity). But if you need to license content or purchase curricula (for example, some colleges license existing online course content or pay for curriculum consulting), allocate funds for that. Also, building out a library of syllabi, assessments, and online course modules might involve small stipends to faculty over the summer before launch. This category is hard to generalize in dollars – it could be minimal (just everyone working to write courses as part of their role) or significant (if you outsource course design, some contractors charge $3k–$5k per course to develop online courseware). We will include library resources in this category too, as “academic content.” A physical or digital library is expected. If you go physical, acquiring a starter collection of books/journals could cost $50,000–$100,000. Most new institutions opt for digital libraries via subscriptions. For example, a subscription to a research database package (like LIRN or JSTOR for small colleges) might be only $2,000 per year for a small student body. That’s a great scalable approach – you can increase the subscription cost as you gain more students.

5. Technology Infrastructure: Modern education runs on technology, especially if you’re online. Key components include a Learning Management System (LMS) for delivering courses, potentially a Student Information System (SIS) for records if the LMS doesn’t handle that, and general productivity and communication tools (email, video conferencing, etc.). For an LMS, you have three routes: open-source (free software like Moodle that you host – but you need tech expertise), SaaS solutions (like Canvas or Blackboard where you pay per user or a license fee), or custom-built. Custom-building an LMS is usually far too expensive for a startup – it can run $25,000–$100,000 just to develop the initial version, plus ongoing costs. Using a ready-made cloud LMS can be more cost-effective: some charge around $5 per student per month (so if you have 100 students, that’s $500/month). There are also free versions of LMS like Canvas for small usage, or Google Classroom if K12 (though for higher ed you’d want more robust systems). Don’t forget to budget for decent computers/servers, high-speed internet, and possibly software licenses (e.g. maybe you need a license for Zoom for online classes, or a plagiarism checker tool for assignments). Upfront, you might spend $5,000–$15,000 on initial IT setup (buying a couple of staff laptops, any necessary servers or paying a web developer, etc.). If you’re doing everything cloud-based, much of the cost will be monthly operational costs (LMS, web hosting, etc.), which might be a few hundred to a couple thousand per month depending on scale.

6. Accreditation and Compliance Costs: While accreditation comes later, preparing for it isn’t free. There are accreditation agency application fees – often a few thousand dollars just to apply, and then costs for site visits (you typically pay evaluator team travel expenses). For example, a regional accreditor might charge $5,000 for an eligibility review, $10,000 for a candidacy application, etc. Plan perhaps $15,000–$30,000 over a couple years for accreditation-related fees and visits. Also, consider legal fees in compliance – you may want a lawyer to review things like your enrollment agreement (contract with students), privacy policy, etc. A lawyer might charge a few hundred per hour; reviewing and drafting key documents might be a couple thousand in total (if using a consultant package, they might include templates for those documents).

7. Marketing and Student Recruitment: “Build it and they will come” does not apply to new colleges. You’ll need to invest in marketing to attract students. Initially, this means creating a professional website (your primary marketing tool), some branding collateral, and advertising. Website development can cost anywhere from a few thousand dollars for a simple but polished site, to $20,000+ for a more complex site with custom features. Let’s say $5,000–$15,000 for a decent website with online application functionality. Then, consider a marketing budget for digital ads (Google, Facebook, maybe LinkedIn if targeting professionals). You could start small, maybe $1,000 per month in online ads targeted to your region or demographic, and ramp up if it works. Content marketing (blogs, social media) mostly costs in staff time, but you might allocate a few thousand to produce some promo videos or do an initial PR press release. If you have the budget, engaging a PR firm to get media coverage can cost a retainer of $5,000–$10,000 per month – probably not in reach for most startups, but maybe for a well-funded one. Keep marketing lean and targeted: it’s better to effectively reach a small pool of likely students (e.g. via specific professional associations or local events) than to spend big on broad campaigns. A good rule is to plan marketing spend per student lead – it might cost hundreds of dollars in advertising per enrolled student when you’re unknown, so plan accordingly in your budget.

8. Miscellaneous and Buffer: There will be many other minor (but adding up) costs: travel for networking or conferences, printing and office supplies, furniture, accreditation workshop fees, etc. It’s wise to include a 10-15% contingency in your budget to cover the unexpected. Also note, many states require you to show a certain minimum amount of operating funds – e.g. enough to run for one year without tuition. That’s often how that “show $100k in the bank” comes into play – not that you spend it all, but you must have it reserved to ensure you won’t fold and strand students. So, ensure you not only budget costs but also secure the funding to cover at least 1-2 years of deficit, because you likely won’t be breaking even on tuition until you reach a certain enrollment which can take a few years.

Let’s summarize some of these costs in a simplified table for an imagined small startup college (adjust up or down for your context):

Note: These are ballpark figures. A lean online-only startup might lean toward the lower end by minimizing facilities and using contractors, whereas a new campus with multiple programs could quickly need the higher end or beyond (especially in salaries and facilities).

Cost Levers (How to Save or Spend Wisely): You have some control over costs through strategic choices. For example, starting online massively reduces facility overhead (as seen, possibly just an office rental instead of campus). Starting with fewer programs means you hire fewer faculty and pay fewer program approval fees; you can always add programs later once revenue comes in. Using open-source solutions (like Moodle for LMS, or free library resources) can lower tech and library costs, albeit at the expense of convenience or requiring IT know-how. DIY vs. done-for-you is a constant trade-off: writing your own policies and managing the accreditation prep yourself saves consultant fees but could cost you time (and potential mistakes). Many successful new institutions invest in a few key areas – typically, quality faculty and solid tech – and economize on others – maybe modest office décor or minimal admin staff until absolutely needed. Also consider phase-wise spending: you don’t have to spend everything at once. Maybe you budget $X for marketing but only unleash it after license approval. Or you plan to upgrade your library and labs in year 3 once you have more students, rather than fully at launch.

Lastly, ensure you have operating capital to sustain the school until it becomes self-sufficient. It’s common for a new college to run at a deficit for the first couple of years while enrollment builds. If you want to avoid surprises, model out a scenario: e.g. “What if we only get 50 students paying $Y tuition in year 1, how much do we lose and can we cover it?” Versus “What if we hit 200 students by year 3, does that break even?” This exercise will tell you how much initial funding to secure. Having a financial cushion is not just good practice – some regulators will ask about it in your application, wanting assurance you won’t financially collapse on students.

In conclusion, opening a college is a significant financial commitment, but with careful planning and scaling, it can be managed. Some have done it on a shoestring by starting very small; others have raised substantial capital to launch big. Whichever route, transparency in budgeting and adequate funding are key – as one education founder put it, “control your money, or it will control you”. Now that we’ve looked at costs, let’s turn to the equally critical side of ensuring academic quality and building credibility – the things that truly set your institution apart in the eyes of students and accreditors.

Ensuring Quality and Credibility from Day One

Getting the doors open is half the battle; making sure what’s inside those doors is excellent is the other half. In higher education, credibility is everything. Students, accreditors, and future employers will judge your college on its academic quality and integrity. This section will cover how to put robust policies and practices in place to ensure you aren’t just compliant, but are delivering education at a standard that gains respect. We’ll also discuss when and how to engage an accreditation consultant and outline a realistic timeline for achieving accreditation.

Academic Policies and the Continuous Improvement Loop: By now, you’ve written policies for state approval – but writing them is just the start. You need to implement and live by them. Key policies to double-check and enforce from day one include:

- Curriculum Governance: Establish a process for reviewing and updating curriculum. For instance, form an Academic Committee (even if small at first) that reviews course syllabi, sets academic standards, and periodically evaluates whether learning outcomes are being met. Document any meetings or decisions – accreditors will later ask, “how do you ensure your courses remain up-to-date and rigorous?” and you’ll want to show meeting minutes or updated syllabi as proof.

- Satisfactory Academic Progress (SAP): If you intend to ever offer federal financial aid, you must have a SAP policy (students must maintain a certain GPA and pace of completion). But even from the start, having an academic probation policy for underperforming students is good practice. Outline how you will evaluate student progress each term, and what interventions (tutoring, counseling) you offer if they fall behind. Most states require you to have a SAP policy in the catalog, and accreditors certainly do.

- Assessment and Outcomes: Plan how you will measure student learning. This could be as granular as course-level outcomes (exams, projects, portfolios) and program-level outcomes (graduation rates, job placement, licensing exam pass rates if applicable). Set targets and collect data. For example, if you say “80% of students will pass the capstone project,” then after your first cohort, calculate it – did 80% pass? If not, discuss what to improve. This assessment loop where you set criteria, measure, and adjust is a cornerstone of accreditation. Start it early even with small numbers.

- Faculty Qualifications and Development: Ensure every instructor’s file has transcripts or proof of their credentials on hand – states often audit this, and accreditors require it. Typically, faculty teaching general education or bachelor’s courses should have a Master’s or higher in the discipline, those teaching Master’s should have a doctorate or terminal degree, etc. If you have any faculty that are borderline (say, a stellar industry professional without a grad degree), be cautious – you might use them in addition to, but not as a replacement for, academically qualified faculty. Also, consider providing training for your instructors, especially if teaching online (e.g. a workshop on using the LMS or on effective online pedagogy). Showing that you invest in faculty development is another credibility marker.

- Academic Integrity: Implement an honor code or academic integrity policy from the start. Even if you trust your initial students, external reviewers will want to see that you take cheating or plagiarism seriously. Use plagiarism detection tools and educate students on proper research conduct. Have a clear process for handling violations (e.g. warning, probation, expulsion).

- Student Support and Services: Don’t skimp on support just because you’re small. Ensure students have channels for academic advising (who helps them pick courses or navigate difficulties?), career advice if relevant, and tech support for online platforms. For instance, if a student has a complaint or grievance, your policy says how it’s handled – make sure in practice someone is designated to receive and resolve complaints. States often require a grievance policy and even ask you to inform students how to contact the state agency if not resolved. So be sure to actually follow that – inform students at orientation or in the catalog where to go with concerns. Early handling of issues prevents bigger problems later.

Accreditation Milestones and Realistic Timeline: Let’s outline a typical timeline for achieving initial accreditation (though it varies by agency):

- Year 0-1: Operate and collect data. Most accreditors require at least 1-2 years of actual operations and often some graduates. For instance, a national accreditor might say you need to have at least one graduating class for a shortest program, or 2 years of classes delivered. Use this time to ensure your state authorization is in good standing (accreditors check that you’re legally approved), and to build a culture of evidence (like we discussed: keep meeting minutes, student performance stats, etc.).

- Choose Accrediting Agency: In Year 1, decide which accreditor to go for. Regional accreditors (now simply institutional accreditors with regional history) like SACS, Middle States, WASC, etc., are the gold standard and cover most non-profit and research-oriented schools. They may have somewhat more stringent expectations and possibly longer processes. National accreditors (like ACCSC, DEAC, ACICS, etc.) often accredit career-oriented or online institutions and might be more accessible for a new, smaller school. Research their reputations and criteria. Some programs might also need programmatic accreditation (for example, if you open a nursing program, you’ll need nursing board approval and maybe nursing accreditation in addition to institutional). That might come later, but be aware of any such needs.

- Year 2: Submit Eligibility or Pre-Application (if required). Many accreditors have an initial screening. You provide basic info to show you meet their minimum requirements (legal status, two years of finances, qualified faculty, etc.). They either invite you to proceed or ask for more development. Once deemed eligible, you become an “Applicant” institution.

- Year 2-3: Enter Candidacy / Provisional Accreditation. Some accreditors grant a candidacy status after an initial self-study and site visit, if you show promise of meeting standards. This is essentially a provisional accreditation – not full recognition, but it tells the world you’re on track. During candidacy, you often can apply for certain benefits like federal aid participation (for some agencies, candidacy or pre-accredited status may allow provisional federal aid – check DOE rules). You will operate under heightened monitoring and continue improving.

- Year 3-4: Achieve Initial Accreditation. After a successful full self-study report and a comprehensive team visit, the accreditor votes to grant you initial accreditation, typically for a shorter first period (like 2-3 years) before your next review. At this point, your students can fully utilize federal financial aid (Pell Grants, loans) if you haven’t already, and credits should transfer more easily to other institutions.

Realistically, that timeline can stretch – if you hit snags, accreditors might defer a decision and ask for more reports, pushing initial accreditation to year 5 or 6. The key is not to rush it; focus on genuinely meeting standards rather than checking boxes. One strategy is to maintain transparency with your students about accreditation status. In the early years, unaccredited institutions often have to disclose to students that they are not yet accredited and thus financial aid is not available. Some schools even reduce tuition during this period to compensate, or offer institutional scholarships, to keep enrollment up until accreditation is secured.

Maintaining Credibility Daily: Beyond the big stuff, credibility is in the little things too. For example, maintain a well-organized website with disclosures (list your state license info, any approvals, faculty bios, etc. – students and regulators will look). Communicate policies clearly to students and enforce them fairly – nothing ruins a college’s rep faster than students feeling misled or mistreated. Handle transcripts and records professionally (e.g., if someone requests a transcript, provide it promptly – and be sure your transcripts look official and include all required info like the school name, credits, signatures, etc.).

Another tip: Start building an institutional track record outside of accreditation. This could be joining professional associations (like CHEA or other higher ed groups as an affiliate), attending conferences, or even having external evaluators review your programs. These actions show you’re serious about quality. Additionally, consider conducting student and alumni surveys to gather testimonials and outcomes data – those positive stories and statistics (e.g. “95% of our first cohort are employed in the field within 6 months”) will be gold for marketing and also for accreditation evidence.

In short, think like an accreditor from day one. Document everything, measure everything, and strive for continuous improvement. Engage help (consultants or mentors from other institutions) when needed to ensure you’re on the right path. Quality isn’t something you implement right before an accreditation visit; it’s a mindset and system you cultivate continuously.

Now, let’s switch gears briefly. We’ve been focusing on higher education (colleges/universities), but perhaps you’re also curious about what it takes to start a K-12 school. Many education entrepreneurs explore both avenues. So, in the next section, we’ll run a parallel track: opening a K-12 school – and highlight how it compares to opening a college.

Parallel Track: Opening a K12 School vs. a College – Similarities and Differences

If your passion for education extends to the K-12 arena (primary and secondary education), you might wonder how opening a K12 school compares to opening a college or university. Many fundamentals are similar – you need a clear mission, a legal entity, and compliance with regulations – but the regulatory environment and practical challenges can differ significantly. Let’s explore the key similarities and differences, keeping in mind both U.S. domestic founders and international investors who might be interested in the U.S. K-12 market.

Regulatory Oversight: Unlike higher education, which is closely regulated in every state, private K-12 schools often face lighter state regulation. The U.S. does not have federal licensing for private schools; it’s all state-based, and many states only have minimal requirements. For example, some states simply ask that you register the school with the state or local education department, maybe filing an annual enrollment report. Other states (a minority) might require a more involved approval or accreditation for private schools. There are even states (like Texas and Oklahoma) that impose virtually no registration requirements on purely private (non-public) K-12 schools – meaning you could open a private school without needing a state license in those places. This is a stark contrast to higher ed, where you cannot legally operate without state authorization.

However, “easier” state requirements come with a trade-off: if no state approval is needed, you lack an official recognition to show parents. That’s why some founders choose states that have at least a simple registration – it lends credibility that the school is known to authorities. (Interestingly, California, which is stringent for colleges, is relatively easy for private K-12: you just file an annual affidavit for a private school, which many home-school umbrella programs do, making it straightforward for an online K-12 venture) International investors launching online private schools have noted that it can be done with as little as $10,000 initial investment precisely because of this lighter regulation – essentially covering business setup and a basic online platform.

Academic Standards and Curriculum: In K-12, you’re dealing with minors and mandatory education laws. Most states require that children receive education in certain subjects (language arts, math, etc.), but private schools often have leeway in curriculum as long as they meet broad standards (unless you’re aiming for some state accreditation or funding which may impose specific curriculum rules). Public K-12 schools have to adhere to state academic standards (Common Core or state-specific standards) and administer state tests. Private schools usually are exempt from state testing, but some choose to voluntarily administer standardized tests (like SAT, ACT, AP exams, or norm-referenced tests) to demonstrate quality. If you’re opening a private K-12, especially one that targets college-bound students, aligning your curriculum with some recognizable standards is wise – it helps ensure students can transition to college smoothly. Also, if you plan to seek accreditation for the school (K-12 accreditation from bodies like Cognia or regional accreditors’ school divisions), you’ll need to follow their curricular and teacher qualification guidelines.

Staffing and Credentials: One big difference: teacher certification requirements. In private K-12, many states do not require teachers to hold state teacher licenses (unlike public schools where it’s mandatory). However, parents may expect certified teachers, and if you want to participate in certain programs (like state school voucher programs), you might need certified staff. Also, for international founders, hiring U.S.-certified teachers can be a selling point. Administrative staff in K-12 includes roles like a Principal/Head of School, guidance counselors, etc. If boarding or in-person, you also consider roles for student welfare (dorm supervisors, nurse, etc.). Ratios of staff to students are important: you might start a small private school with a handful of teachers covering multiple grades, but as you grow, you’ll need to keep class sizes reasonable to attract parents.

Safeguarding and Student Welfare: Running a school for minors comes with heavy responsibilities for safety and welfare. This includes background checks for all employees (virtually every state requires private school employees to undergo criminal background checks/fingerprinting – it’s non-negotiable when working with kids). You’ll need policies for preventing and reporting abuse, safety drills (fire, lockdown procedures), and likely have to comply with local health and safety codes (for example, if you serve food, the cafeteria must meet health department standards; if you have a lab, handle chemicals safely; playground equipment must be up to code, etc.). If boarding (residential school), that’s an entire layer of regulation and risk management (dorm supervision, 24/7 care, etc.). Even for an online K-12 school, consider cyber safety and parental consent for online activities since your students are minors.

Licensing and Accreditation (K-12): While state licensure might be minimal, many private K-12 schools voluntarily pursue accreditation through organizations like Cognia (formerly AdvancED), regional accrediting agencies (the same names that accredit colleges often have K-12 divisions), or specialized private school accreditors. Accreditation in K-12 isn’t required by law, but it can help with prestige, credit transfer (like if a student transfers from your school to another, or for college admissions confidence), and sometimes with eligibility for state programs. The timeline for K-12 accreditation is often shorter than for colleges – you might get candidacy within a year of operating and full accreditation by year 2 or 3 if all goes well. If you’re planning an international curriculum (like offering International Baccalaureate or Cambridge IGCSE/A-Levels), those come with their own authorization processes too.

Funding and Market: In K-12, your revenue model is typically tuition (unless you’re running a charter school or something public, which is a whole different process involving government approval and oversight). Many U.S. states now have or are expanding school choice programs (vouchers or scholarships) that allow public education funds to pay for private school tuition. If you operate in such a state and get your school approved for those programs, it can boost enrollment (families get state assistance to attend your school). For instance, states like Florida or Arizona have scholarship programs for private school students; being part of that can be a game-changer for enrollment. However, joining those programs might require certain accountability measures (standardized testing or financial audits), effectively increasing your regulatory burden a bit. As an investor, note that the K-12 space is seeing growth due to these programs and parent demand for alternatives, as one consultant noted – there’s “unprecedented demand for opening a K12 school” with trends like safety concerns and personalized education driving interest.

Timeline to Open a K-12 School: It can often be faster than a college. You need to incorporate, possibly find a facility (if physical – location is crucial for a school because parents consider commute and neighborhood), hire teachers, develop curriculum (or choose a curriculum package), and market to parents. If licensing is minimal, you could feasibly go from plan to opening in less than a year – many small private schools do. However, if you require building a facility, factor in time for renovations and inspections. Also, school years have fixed calendars – most open in late summer/fall, so you often time your launch to an academic year. If you miss that, you typically wait till the next year (unless it’s an online rolling-enrollment model).

International Students (K-12): If you plan to bring in international students (for an American boarding school experience, for example), you’ll need SEVP certification (similar to colleges) to issue F-1 visas. That requires being in operation and meeting certain criteria, including accreditation eventually. That’s a longer-term goal (you usually need to be running for a bit before applying).

Similarities: In both college and K-12 startup, you need a clear mission, a sustainable financial plan, good marketing, and a genuine commitment to student outcomes. Community engagement matters in both – be it with parents or with local stakeholders. And in both, you should start small, establish quality, and then expand. Interestingly, some entrepreneurs start a K-12 school and later add a junior college, or vice versa, creating an education ecosystem. While regulations differ, the core challenge is the same: delivering value to students and earning trust.

To wrap this section: Opening a K-12 school shares the entrepreneurial spirit of opening a college but plays out in a different regulatory sandbox. The hurdles are less about accreditation and more about finding your niche in a competitive and sometimes emotionally-charged market (parents care deeply about who educates their kids!). If you can navigate local regulations (or lack thereof) and build a strong parent community, a K-12 school can be quicker to establish, albeit with its own intense responsibilities (children’s safety and growth). Many of our earlier steps (entity setup, business plan, etc.) apply equally to K-12, just adapted to school specifics. And as noted, on the cost side, an online private K-12 could start with surprisingly low capital (tens of thousands), whereas a full brick-and-mortar K-12 campus could be multi-millions (think buying land, sports facilities, etc.). So scope matters.

Now that we’ve covered both tracks – higher ed and K-12 – let’s bring this guide toward a close with a brief case study to illustrate how all these pieces come together in real life, and then a checklist and pitfalls to ensure you’re truly ready to open your educational venture.

Case Study: From Vision to Reality – Summit Hills University

To illustrate the journey, let’s look at a hypothetical (but realistic) case study.

Founder Profile & Vision: Meet Dr. Elena Rodríguez and Mr. Michael Thompson. Elena is a former associate dean at a community college with 15 years of academic administration experience. Michael is an entrepreneur who sold his tech startup and wants to invest in education. Together, in 2020, they envisioned Summit Hills University, a private non-profit university focused on environmental sustainability and renewable energy programs. Their target students are working adults and recent graduates in Latin America and the U.S. who want specialized online master’s degrees in sustainability (though the institution would be U.S.-based and confer U.S. degrees). They chose this niche because Elena noticed a gap: traditional universities weren’t offering enough applied, online programs in this field, and industry employers were desperate for talent.

Timeline & Milestones:

- Early 2021 (Planning Phase): Elena and Michael conducted market research. They consulted renewable energy companies and confirmed strong interest in courses that blend engineering, policy, and business skills. They also studied SEO data and saw many searching “how to open a college or university” – this ironically led them to resources (and to hiring an accreditation consultant down the line). They incorporated Summit Hills University as a non-profit in Delaware (known for flexible corporate laws) and then foreign-registered in Colorado, the state they chose to base operations. Why Colorado? It’s part of SARA (good for online reach), has a reasonable authorization process, and is branding-friendly (Colorado is associated with green initiatives, aligning with their mission). They assembled a preliminary Board of Trustees including a former university president (as board chair), a CFO of a solar company, and a local community leader. By June 2021, they had a detailed business plan and seed funding of $500,000 (Michael’s investment plus a small grant from a green energy foundation that loved their idea).